Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Early Years (1916-1919)

- Initial focus on popular and classical music

- Development of recording techniques

- Building a distribution network

- The Breakthrough Years (1920-1924)

- Introduction of “race records” series

- Expansion into country music (“hillbilly” records)

- . Key artists and recordings

- Marketing and Distribution Strategies

- Challenges and Changes

- Impact of the Great Depression

- Acquisition by Columbia Phonograph Company (1926)

- Discontinuation as independent label (1935)

- Suggested Listening

- Also in Vintage Record Labels

Okeh Records: Pioneering Sounds in American Music (1916-1935)

Introduction

In the dynamic landscape of early 20th century American music, Okeh Records emerged as a transformative force, its impact reverberating far beyond its relatively short lifespan. Founded in 1916 and operating independently until 1935, Okeh wasn’t just another player in the burgeoning record industry—it was a trailblazer that helped democratize music production and consumption in ways that continue to influence the industry today.

Okeh Records sprang from the entrepreneurial mind of Otto K. E. Heinemann, a German-American businessman who saw untapped potential in the American music market. Unlike many of his contemporaries who focused solely on popular mainstream music, Heinemann envisioned a label that would cast a wider net, capturing the diverse sounds emanating from every corner of the nation. The name “Okeh”—a phonetic spelling of “okay” derived from Heinemann’s initials—would soon become a stamp of quality and innovation in the recording world.

What set Okeh apart was not just its willingness to record a wide array of genres, but its pioneering approach to discovering and promoting talent. This was the label that introduced the world to Louis Armstrong’s hot jazz, that gave voice to rural blues artists, and that helped popularize country music (then known as “hillbilly music”) beyond its regional origins. Okeh’s “race records” series, launched in 1920, was groundbreaking in its focus on African American artists and audiences, paving the way for future recognition and appreciation of these crucial contributions to American music.

But Okeh’s influence extended beyond its artist roster. The label was at the forefront of recording technology, experimenting with mobile recording units that could capture authentic regional sounds on location. Its marketing strategies, particularly in reaching African American audiences, set new standards in the industry. Through all of this, Okeh Records didn’t just reflect the sounds of America—it played an active role in shaping them.

Certainly! Here’s the section on the early years of Okeh Records:

Early Years (1916-1919)

When Otto Heinemann launched Okeh Records in 1916, the American recording industry was still in its relative infancy. The early years of Okeh were characterized by cautious expansion, technological experimentation, and the gradual development of a unique identity in a competitive market.

Initial focus on popular and classical music

In its nascent stage, Okeh Records adhered to a conventional approach, focusing primarily on popular and classical music. This strategy was driven by the prevailing market demands and the tastes of middle-class Americans who constituted the primary consumers of phonograph records.

The label’s early catalog featured a mix of contemporary pop tunes, light classical pieces, and operatic arias. Dance music was particularly popular during this period, with Okeh releasing numerous recordings of waltzes, fox-trots, and one-steps. The label also capitalized on the patriotic fervor of World War I, issuing several martial and patriotic songs that resonated with the public mood.

Development of recording techniques

Okeh’s early years coincided with a period of rapid technological advancement in sound recording. The label, under Heinemann’s guidance, invested significantly in improving its recording techniques.

Initially, Okeh used the standard acoustic recording method of the time, where performers would crowd around a large horn that funneled sound waves to a diaphragm, which in turn vibrated a cutting stylus that etched the sound onto a wax disc. However, Okeh’s engineers continually experimented with horn designs, diaphragm materials, and cutting techniques to improve sound quality.

By 1919, Okeh had developed a reputation for producing records with notably clear sound. This attention to technical quality would become one of the label’s hallmarks and a key factor in its growing success.

Building a distribution network

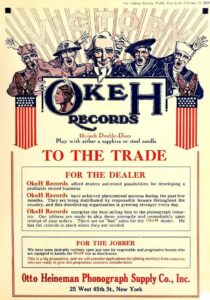

Perhaps one of the most crucial aspects of Okeh’s early development was Heinemann’s focus on building a robust distribution network. Unlike larger companies that owned their own stores or had established distribution channels, Okeh had to create its network from scratch.

Heinemann leveraged his business acumen and contacts in the phonograph industry to secure deals with independent dealers across the country. He also implemented an aggressive pricing strategy, often undercutting competitors to gain market share.

Additionally, Okeh developed a mail-order catalog system, allowing customers in rural areas to order records directly. This approach would later prove instrumental in the label’s success with “hillbilly” and “race” records, reaching audiences underserved by traditional urban-centric distribution models.

By 1919, Okeh had established itself as a serious contender in the record business. Its growing catalog, improving sound quality, and expanding distribution network set the stage for the breakthrough years that were to follow. Little did anyone know that in the coming decade, Okeh would not just participate in the music industry—it would help revolutionize it.

Certainly! Here’s the section on the breakthrough years of Okeh Records:

The Breakthrough Years (1920-1924)

The period from 1920 to 1924 marked a transformative era for Okeh Records, during which the label made bold moves that would not only ensure its commercial success but also significantly impact the landscape of American popular music.

Introduction of “race records” series

Mamie Smith’s “Crazy Blues” (1920)

The watershed moment for Okeh came in August 1920 with the release of Mamie Smith’s “Crazy Blues.” This recording is widely recognized as the first vocal blues record by an African American artist. The decision to record Smith was partly due to the persistence of Perry Bradford, an African American songwriter and music publisher who convinced Okeh’s Fred Hager to take a chance on recording a black artist singing blues.

“Crazy Blues” was an immediate sensation, reportedly selling 75,000 copies in its first month and eventually surpassing sales of one million. This unprecedented success opened the eyes of Okeh and other record companies to the untapped potential of the African American market.

Impact on African American music recording

The success of “Crazy Blues” led Okeh to establish its 8000 “race records” series, specifically targeting African American audiences. This move was revolutionary, as it marked the first time a major label had dedicated an entire series to black artists and listeners.

The “race records” series quickly expanded beyond blues to include jazz, spirituals, and other forms of African American music. It provided a platform for numerous talented black artists who had previously been overlooked by the mainstream recording industry.

Expansion into country music (“hillbilly” records)

Riding on the success of its “race records,” Okeh also ventured into another underserved market: rural white audiences. In 1923, Okeh talent scout Ralph Peer discovered fiddler John Carson and recorded “Little Old Log Cabin in the Lane” / “The Old Hen Cackled and the Rooster’s Going to Crow.” This marked Okeh’s entry into what would later be known as country music, then termed “hillbilly” music.

The success of Carson’s records led to the creation of Okeh’s 45000 series for “hillbilly” music, paralleling the 8000 series for “race records.” This move helped establish country music as a commercially viable genre and played a crucial role in bringing rural Southern music to a wider audience.

. Key artists and recordings

During this period, Okeh recorded a remarkable roster of artists across various genres:

- Blues and Jazz: Besides Mamie Smith, Okeh recorded such seminal artists as Louis Armstrong, King Oliver, Sidney Bechet, and Lonnie Johnson. Armstrong’s Hot Five and Hot Seven recordings for Okeh in the mid-1920s are considered some of the most important jazz recordings of all time.

- Country: Following the success of Fiddlin’ John Carson, Okeh recorded other early country stars like Henry Whitter and Charlie Poole.

- Popular music: Okeh continued to record mainstream pop and dance band music, featuring artists like Vincent Lopez and His Hotel Pennsylvania Orchestra.

These breakthrough years established Okeh as a major force in the recording industry. By recognizing and serving previously overlooked markets, Okeh not only ensured its own commercial success but also played a crucial role in the development and dissemination of blues, jazz, and country music. The label’s willingness to record a diverse range of artists and musical styles set a new standard in the industry and helped shape the course of American popular music for decades to come.

Marketing and Distribution Strategies

Okeh Records’ success wasn’t solely due to its impressive roster of artists or its technological innovations. The label’s marketing and distribution strategies played a crucial role in its rise to prominence and its ability to reach diverse audiences across the United States and beyond.

Innovative advertising in African American newspapers

Okeh was one of the first record labels to recognize the importance of targeted marketing to African American audiences. Following the success of its “race records” series, the label began placing regular advertisements in prominent African American newspapers such as the Chicago Defender, the Pittsburgh Courier, and the Baltimore Afro-American.

These advertisements were revolutionary in several ways:

- Visual appeal: Okeh’s ads often featured bold, eye-catching graphics and illustrations that stood out on the page. Many ads included portraits of the artists, helping to create a visual connection with potential buyers.

- Targeted language: The copy in these ads often used colloquialisms and phrases familiar to African American readers, creating a sense of cultural affinity.

- Emphasis on authenticity: Okeh frequently promoted its artists as genuine representatives of African American music, emphasizing their roots and authenticity.

- New release information: The ads kept readers informed about new releases, creating anticipation and driving sales.

This targeted advertising approach helped Okeh build a loyal customer base within the African American community and set a new standard for marketing in the record industry.

Mail-order catalogs

Recognizing that many potential customers, particularly in rural areas, didn’t have easy access to record stores, Okeh developed an extensive mail-order catalog system. These catalogs were crucial in reaching audiences for both their “race records” and “hillbilly” series.

The catalogs typically included:

- Comprehensive listings of available recordings

- Descriptions of the music and artists

- Pricing information

- Order forms and instructions

This direct-to-consumer approach allowed Okeh to reach customers in areas underserved by traditional retail outlets, significantly expanding their market reach.

International distribution

While many American record labels of the time focused primarily on the domestic market, Okeh took steps to distribute its recordings internationally. This strategy was partly influenced by Otto Heinemann’s international background and connections.

- European distribution: Okeh established distribution partnerships in several European countries, particularly for its jazz recordings, which were gaining popularity overseas.

- Latin American market: Recognizing the growing market for music in Latin America, Okeh began recording and distributing Latin music, including tango and rhumba recordings.

- Export series: Okeh created special export series for international markets, often featuring recordings that had proven popular in the United States.

- Licensing agreements: In some cases, Okeh entered into licensing agreements with foreign record companies to manufacture and distribute Okeh recordings in their local markets.

This international approach not only increased Okeh’s revenue streams but also played a role in spreading American musical styles, particularly jazz, to global audiences.

Okeh’s innovative marketing and distribution strategies demonstrated the label’s adaptability and foresight. By targeting specific demographics, embracing direct-to-consumer sales, and looking beyond U.S. borders, Okeh was able to maximize the reach of its diverse catalog and play a significant role in shaping the global music landscape of the early 20th century.

Challenges and Changes

Despite its innovative approaches and successes in the 1920s, Okeh Records faced significant challenges in the following decade that would ultimately lead to the end of its run as an independent label.

Impact of the Great Depression

The stock market crash of 1929 and the ensuing Great Depression had a profound impact on the entire recording industry, and Okeh was no exception.

- Declining sales: As unemployment soared and disposable incomes plummeted, record sales across the industry dropped dramatically. Okeh’s core audiences, including working-class African Americans and rural whites, were particularly hard hit by the economic downturn.

- Production challenges: The economic crisis forced Okeh to cut back on production, reducing the number of new releases and limiting the resources available for discovering and promoting new talent.

- Shifting consumer habits: With less money to spend on entertainment, many consumers turned to radio as a free alternative to purchasing records, further impacting Okeh’s sales.

- Artist retention: Financial constraints made it difficult for Okeh to retain some of its top artists, with several being lured away by larger labels or leaving the music industry altogether.

Acquisition by Columbia Phonograph Company (1926)

Even before the onset of the Great Depression, Okeh had undergone a significant change in ownership:

- Sale to Columbia: In 1926, Otto Heinemann sold Okeh Records to Columbia Phonograph Company, a larger and more established competitor.

- Initial autonomy: Following the acquisition, Okeh was initially allowed to operate with a degree of autonomy, maintaining its own artist roster and release schedule.

- Gradual integration: Over time, Columbia began to more closely integrate Okeh’s operations with its own, leveraging Okeh’s strength in blues and country music to complement Columbia’s existing catalog.

- Technological sharing: The acquisition allowed Okeh to benefit from Columbia’s more advanced recording technologies, including improved electrical recording techniques.

Discontinuation as independent label (1935)

The combination of economic pressures and corporate restructuring eventually led to the end of Okeh as an independent entity:

- Corporate consolidation: In 1934, the American Record Corporation (ARC) acquired Columbia, including the Okeh subsidiary. ARC began consolidating its various labels to cut costs.

- End of independent operations: In 1935, ARC made the decision to discontinue Okeh as an independent label. The Okeh name was temporarily retired, and many of its artists were shifted to other ARC labels.

- Legacy preservation: Despite the discontinuation, much of Okeh’s catalog was preserved and continued to be reissued under various Columbia and ARC imprints.

- Later revivals: The Okeh name would be revived several times in later decades, often as a subsidiary label focusing on particular genres, but never again with the independence and influence it had in its early years.

The story of Okeh’s challenges and ultimate discontinuation as an independent label reflects the broader turmoil in the recording industry during the 1930s. Economic hardship, technological changes, and industry consolidation reshaped the landscape of American recorded music. While Okeh’s run as an independent force in the industry came to an end, the impact of its innovations in recording, marketing, and distribution, as well as its role in popularizing blues, jazz, and country music, would continue to influence the music industry for decades to come.

Suggested Listening

12th Street Rag

Fee Fi Fo Fum

Deedle Deedle Dum

Baby You Made Me Fall For You

Down in Happy Valley

Echos of the Dance