Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Plot Overview

- Themes and Messages

- Performances

- Cinematography and Direction

- Cultural and Historical Context

- Conclusion

Introduction

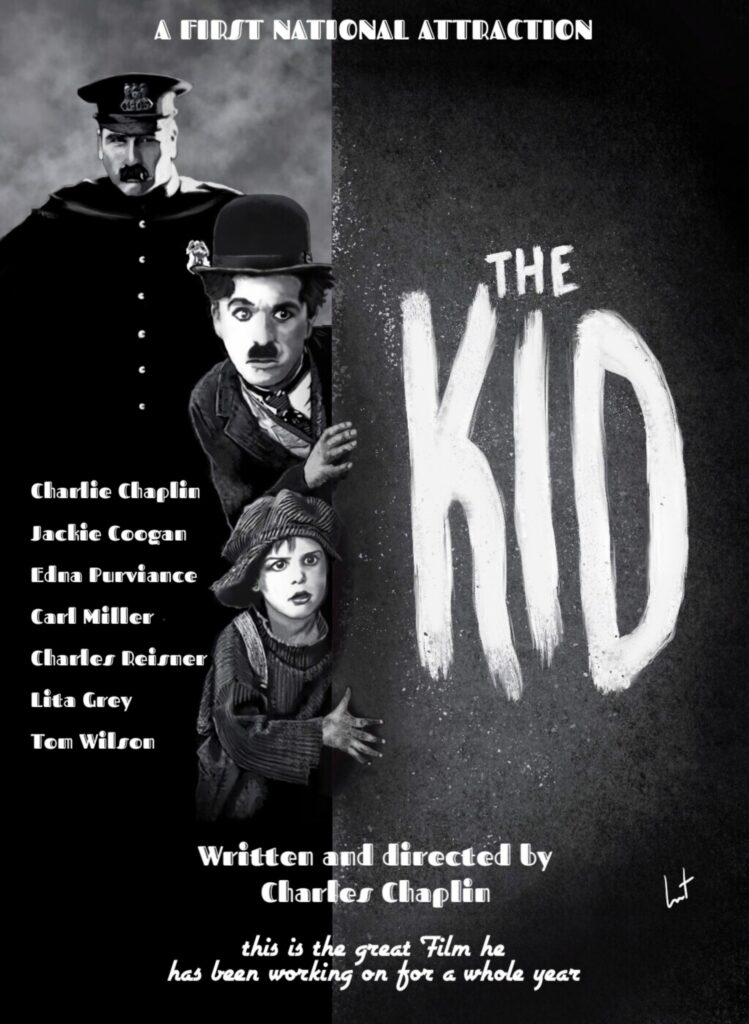

Few figures in cinematic history are as universally recognized as Charlie Chaplin, the pioneering filmmaker and actor whose signature character, The Tramp, became an enduring symbol of silent cinema. In 1921, Chaplin released his first full-length feature film, The Kid, which not only solidified his reputation as a master of blending comedy with heartfelt drama but also marked a milestone in film history.

The Kid tells the story of an unlikely bond between a wandering vagabond (played by Chaplin himself) and an abandoned child (portrayed by the brilliant Jackie Coogan). More than just a showcase for Chaplin’s genius in physical comedy, the film is an exploration of poverty, love, and the trials of parenthood, infused with Chaplin’s trademark social commentary. Released during the early 1920s, a time when the world was grappling with the aftermath of World War I, The Kid provided audiences with an emotional escape while also addressing the harsh realities faced by the urban poor.

As one of the earliest films to successfully blend humor and pathos, The Kid remains a significant achievement in cinematic storytelling and continues to resonate with audiences today.

Plot Overview

The Kid opens with a heart-wrenching scene: a destitute woman, unable to care for her newborn child, leaves him in the backseat of a wealthy family’s car, hoping they will give him a better life. However, fate intervenes when the car is stolen, and the child is abandoned in the streets. Enter Charlie Chaplin’s beloved character, The Tramp, a wandering vagabond with little to his name but a kind heart. He discovers the baby, and after a series of failed attempts to pass the child off to others, The Tramp decides to care for him himself.

As the boy, named John (The Kid), grows up, the two form a close, father-son bond, surviving together in the slums through a mix of ingenuity and mischief. They make a living by pulling off a comical scam: The Kid breaks windows, and The Tramp shows up shortly afterward as a glazier, offering to fix them. Though poor, they share a life of humor, camaraderie, and love.

The tranquility of their lives is shattered when authorities, deeming The Tramp an unfit guardian, attempt to take The Kid away. This leads to one of the most poignant scenes in silent film history, as The Tramp desperately tries to reunite with the child he has come to love as his own. Meanwhile, The Kid’s biological mother, now a successful actress, begins to search for her lost son, unaware that he has been raised by The Tramp.

The film climaxes with a dramatic chase and a heartfelt reunion, ending with The Tramp and The Kid arriving at the mother’s house, suggesting that a new, unconventional family might form. The blend of slapstick comedy and deep emotional moments makes The Kid a touching tale of resilience, love, and survival in a harsh, indifferent world.

Themes and Messages

At its core, The Kid is a film about human resilience and the bonds that form in the most unlikely of circumstances. One of the film’s central themes is the idea of found family—how love and care can emerge not just from blood relations, but from shared experiences and the deep need for connection. The relationship between The Tramp and The Kid is built on mutual need, but it transcends mere survival; it becomes an expression of unconditional love. Through their bond, Chaplin explores the ways in which people create family in a world that often neglects the vulnerable.

Poverty is another key theme running through The Kid. Chaplin, who himself grew up in extreme poverty in London, portrays the struggles of the urban poor with a deep sense of empathy. The film captures the stark realities of those living on the margins of society, from the cramped, dilapidated apartment The Tramp and The Kid share, to the humiliating intrusion of social services attempting to break up their makeshift family. Through these scenes, Chaplin subtly critiques the way society treats its poorest citizens, especially orphans and single parents, revealing a compassion that elevates the film beyond mere comedy.

The film also explores abandonment and redemption. The Kid’s biological mother, who leaves him out of desperation, represents a societal failure to care for those who cannot care for themselves. Her later redemption, as she attempts to find her lost child, suggests that guilt and the yearning for atonement are deeply human emotions. The Tramp, too, is a figure of redemption, taking on the responsibility of caring for The Kid despite his own dire circumstances.

Lastly, The Kid embodies Chaplin’s signature blend of sentimentality and comedy. He skillfully balances moments of light-hearted humor with deeply emotional scenes, ensuring that the film’s pathos never becomes overly saccharine. In fact, the comedic elements—such as The Kid breaking windows or The Tramp’s bumbling attempts at fatherhood—serve to heighten the emotional depth by making the characters more relatable and their struggles more poignant. Through this delicate balance, Chaplin sends a powerful message: humor and hardship often coexist, and it is through humor that we can endure the toughest of times.

Performances

At the heart of The Kid is the unforgettable performance of Charlie Chaplin, whose portrayal of The Tramp is as endearing as it is iconic. By 1921, Chaplin had already perfected his role as the lovable vagabond, a character defined by his trademark bowler hat, cane, and comically oversized shoes. But in The Kid, Chaplin deepens the character by infusing him with a new level of emotional complexity. While The Tramp still engages in his familiar physical comedy, full of clever gags and slapstick routines, it’s his tender, fatherly moments with The Kid that leave a lasting impression. Chaplin masterfully conveys a range of emotions—joy, desperation, and heartbreak—often without uttering a single word, a testament to his prowess in silent film acting.

However, it’s Jackie Coogan, as The Kid, who truly steals the show. Only six years old at the time of filming, Coogan delivers a remarkably nuanced performance that stands out as one of the earliest examples of genuine child acting in cinema. Coogan’s ability to match Chaplin’s physical comedy while also delivering raw emotion, especially in scenes where The Kid is separated from The Tramp, is nothing short of extraordinary. His expressive face and natural charm allow the audience to connect deeply with the character, making the bond between The Kid and The Tramp feel all the more real. Coogan’s performance was groundbreaking, and it set a new standard for child actors in Hollywood.

The supporting cast, while not as prominent, plays an important role in shaping the film’s narrative. Edna Purviance, who plays The Kid’s biological mother, brings a quiet sense of sorrow and dignity to her role, providing the emotional anchor to the subplot of her eventual reunion with her son. Purviance’s performance complements Chaplin’s direction, as her character embodies the heartbreak of abandonment and the hope for redemption.

Together, the performances in The Kid blend physical comedy with profound emotion, resulting in a film that feels both intimate and universal. Chaplin and Coogan’s on-screen chemistry is the driving force of the film, and their performances remain as fresh and moving today as they were over a century ago.

Cinematography and Direction

Charlie Chaplin’s direction in The Kid showcases his mastery of visual storytelling, seamlessly blending slapstick comedy with moments of deep emotional resonance. The film’s cinematography, though relatively simple by today’s standards, is highly effective in conveying both the grim realities of life for the poor and the warmth of the bond between The Tramp and The Kid. Chaplin, who often took on multiple roles in his films, including writer, director, and actor, imbues every scene with a sense of intentionality, using the camera not just to capture physical action, but to enhance the emotional undercurrents of the story.

One of the standout aspects of the film’s direction is Chaplin’s ability to balance the comedic with the dramatic. For example, the film’s opening sequence—where The Tramp tries and fails to rid himself of the abandoned baby—is filled with physical comedy and visual gags, yet it never loses its underlying emotional weight. Chaplin’s use of close-ups, particularly during moments of intimacy or despair, allows the audience to connect more deeply with the characters, making the comedic moments feel more human and the dramatic moments more poignant.

The cinematography captures the stark contrast between the vibrant inner world of The Tramp and The Kid and the bleakness of their surroundings. Their cramped, rundown apartment is a symbol of their poverty, but it also becomes a space filled with laughter and love, thanks to Chaplin’s direction. He cleverly uses this setting to highlight the tenderness in their relationship, turning mundane tasks like meal preparation or bedtime into charming and comedic moments that resonate with the audience.

One of the most visually striking scenes in the film is the dream sequence toward the end, where The Tramp envisions a utopian neighborhood filled with angels. This sequence, though surreal and fantastical, serves as a metaphor for The Tramp’s longing for a better life, not just for himself but for The Kid. The contrast between this heavenly dream and the harsh realities of their life in the slums further deepens the film’s emotional complexity. The use of special effects in this sequence was groundbreaking at the time and demonstrates Chaplin’s innovative approach to filmmaking.

Throughout The Kid, Chaplin’s camera movements are subtle but deliberate, often framing scenes in a way that emphasizes the isolation and vulnerability of his characters. The famous sequence where The Kid is forcibly taken away by the authorities is a prime example: the camera focuses on The Tramp’s frantic chase, with wide shots that emphasize the physical and emotional distance between him and The Kid, heightening the tension and despair of the moment.

In The Kid, Chaplin proves that his skills as a director are just as formidable as his talents as an actor. His ability to craft a narrative that is visually compelling while also deeply emotional makes the film a cinematic triumph, one that continues to influence filmmakers today.

Cultural and Historical Context

Released in 1921, The Kid arrived during a time of significant social and cultural change in the United States and across the world. The aftermath of World War I had left economies struggling, and urban poverty was widespread. For many, the harsh realities of life were reflected in their day-to-day experiences, especially in rapidly growing cities where the wealth gap was stark. It is within this context that The Kid finds its resonance, using the backdrop of poverty and abandonment to tell a deeply human story.

Charlie Chaplin, who grew up in extreme poverty in London, was no stranger to the challenges faced by the working class. His own life experiences informed much of his work, and in The Kid, he uses The Tramp’s struggles to reflect the broader societal issues of the time. The film’s portrayal of the lower-class urban environment, with its cramped living conditions, meager meals, and daily struggle for survival, would have been all too familiar to audiences in the early 1920s. By showing the vulnerability of the poor and the resilience they develop, Chaplin created a narrative that many could relate to, despite its comedic framing.

Another significant element of The Kid is its focus on the plight of orphans and abandoned children. The early 20th century saw a rise in urbanization, and with it came an increase in homelessness and child abandonment. The lack of social safety nets meant that many children were left to fend for themselves, or worse, taken in by institutions that were often harsh and unsympathetic. Chaplin, through his portrayal of The Kid’s near separation from The Tramp by social workers, critiques these institutions and the impersonal nature of the bureaucracies that governed them. His message is clear: love and care, not just legal authority, are what make a family.

The film also reflects the changing role of women in society. Edna Purviance’s character, The Kid’s mother, represents the many women who found themselves abandoned or unsupported by society when they became unwed mothers. Her decision to leave her child in the hope of giving him a better life, and her subsequent success as an actress, touches on the evolving opportunities for women in the workforce and public life during the 1920s, yet also highlights the deep moral and emotional dilemmas they faced.

Conclusion

Charlie Chaplin’s The Kid remains a timeless masterpiece, a film that continues to resonate with audiences over a century after its release. With its seamless blend of humor and heart, it transcends the limitations of silent cinema, telling a deeply human story that feels just as relevant today as it did in 1921. Chaplin’s portrayal of The Tramp, a figure of both comedy and compassion, and Jackie Coogan’s groundbreaking performance as The Kid form the emotional core of the film, creating a dynamic that is both tender and profoundly moving.

Through its exploration of poverty, abandonment, and the resilience of the human spirit, The Kid offers a powerful social commentary while also delivering moments of joy and laughter. Chaplin’s ability to turn everyday struggles into cinematic gold, balancing slapstick with sentimentality, is a testament to his genius as both an actor and a director. The Kid is not just a film about survival—it is a celebration of love, family, and the power of human connection, reminding us that even in the harshest of circumstances, there is always room for kindness and hope.

Whether you are a longtime fan of silent cinema or discovering Chaplin for the first time, The Kid is a must-watch. It remains one of the defining films of the silent era and a shining example of Chaplin’s enduring legacy as a filmmaker who could make us laugh, cry, and think—all at the same time.