Table of Contents

- Production Design and Visual Achievement

- Lon Chaney

- Themes

- Directorial Choices and Cinematic Techniques

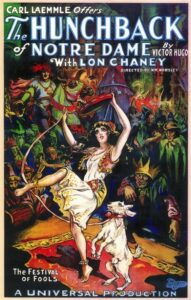

The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) stands as one of silent cinema’s towering achievements, blending grandiose production with a raw, emotional power that captivated audiences and critics alike. Directed by Wallace Worsley, this adaptation of Victor Hugo’s novel brought medieval Paris to life with unprecedented scale and detail, offering a haunting vision of a world both beautiful and brutal. At the heart of this film is Lon Chaney’s legendary portrayal of Quasimodo, a performance that would forever mark him as “The Man of a Thousand Faces.” With its innovative production, memorable performances, and timeless themes of empathy and isolation, The Hunchback of Notre Dame is a film that established Universal Pictures as a major force in Hollywood, setting a new standard for epic storytelling and leaving an indelible mark on cinematic history.

Production Design and Visual Achievement

One of the most impressive feats of The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) is the massive, meticulously crafted set that recreated Notre Dame Cathedral in extraordinary detail. Built on the Universal Studios lot, this ambitious replica was one of the largest and most intricate sets ever constructed at the time, with towering spires, labyrinthine staircases, and brooding gargoyles that captured the imposing Gothic beauty of the real Notre Dame. This environment was more than just a backdrop—it played an essential role in establishing the film’s dark, immersive atmosphere, making the cathedral itself feel like a character in the story.

The attention to detail brought medieval Paris to life with vivid authenticity, allowing audiences to step back into a world of shadow and stone, where the line between the sacred and the sinister often felt blurred. This sense of place elevated the film’s Gothic tone, accentuating the themes of beauty, deformity, and isolation at the heart of Victor Hugo’s novel. The sprawling set not only helped ground Quasimodo’s tragic story in a convincing reality but also gave the film a sense of scale and drama that was unparalleled at the time.

With The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Universal Pictures set a high bar for cinematic spectacle. The film was a testament to the studio’s ambition and became a landmark achievement that helped solidify Universal’s reputation for large-scale, visually stunning productions. This dedication to detail and grandeur would become a hallmark of Universal’s later successes, laying the groundwork for the studio’s golden age of horror and setting a precedent for Hollywood’s future epics.

Lon Chaney

At the heart of The Hunchback of Notre Dame is Lon Chaney’s unforgettable portrayal of Quasimodo, a role that solidified his legacy as “The Man of a Thousand Faces.” Known for his incredible ability to physically transform for each role, Chaney had already built a reputation in Hollywood for taking on characters who were as grotesque as they were deeply human. In Quasimodo, Chaney found a role that demanded both extreme physical dedication and profound emotional depth, resulting in a performance that would become one of the defining portrayals of silent cinema.

To embody Quasimodo, Chaney went to extraordinary lengths. He wore a heavy harness that twisted his body into the hunchback’s infamous contortion, adding an uncomfortable realism to the character’s movement. His face was transformed through elaborate makeup, including a prosthetic eye that altered his expression and contributed to the character’s asymmetry and haunting appearance. These transformations weren’t mere disguises; they were tools that Chaney used to convey the intense physical suffering and isolation of Quasimodo, making the character’s pain palpable to audiences even without a word spoken.

Yet Chaney’s true genius lay in his ability to reveal the humanity beneath the grotesque exterior. Through subtle facial expressions, longing gazes, and a remarkable use of gesture, Chaney infused Quasimodo with a poignant vulnerability that resonated with viewers. His performance captured the loneliness and yearning of a character shunned by society but capable of deep love and loyalty. Even amid the lavish production and grandiose sets, Chaney’s Quasimodo was the film’s emotional anchor, conveying the character’s inner beauty and tragedy with a power that transcended the limitations of silent film. In his hands, Quasimodo became more than a tragic figure; he became a symbol of resilience, love, and the painful search for acceptance in a world that saw only his deformity.

Themes

At its core, The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) is a tale of social exclusion and the human need for empathy, themes drawn directly from Victor Hugo’s novel and brought to life with intensity in Wallace Worsley’s adaptation. The film explores a society that cruelly marginalizes those who do not fit its narrow definitions of beauty and normalcy, embodied in the figure of Quasimodo, whose deformity makes him a target of fear, ridicule, and prejudice. This portrayal of social alienation speaks not only to Quasimodo’s suffering but also to the broader tendency of societies to isolate and dehumanize those who are different.

Quasimodo’s relationship with Esmeralda, the beautiful and compassionate gypsy played by Patsy Ruth Miller, becomes the emotional heart of the film and offers a powerful lens through which to examine themes of inner beauty and societal judgment. Unlike the rest of Paris, Esmeralda sees beyond Quasimodo’s appearance and connects with him as a person, not a monster. This bond between the two outcasts is marked by a mutual understanding and respect, with Quasimodo’s loyalty and love for Esmeralda growing out of her rare kindness toward him. Their relationship underlines the film’s central message: that genuine beauty is found not in appearances but in compassion and acceptance.

These themes of empathy, love, and the search for human connection transcend time and remain just as relevant today as they were in 1923. Quasimodo’s experience as an outsider speaks to the universal struggle for acceptance and the pain of rejection, resonating with anyone who has felt misunderstood or marginalized. The film invites viewers to look beyond the surface, challenging them to question societal standards and to recognize the worth and humanity in others. By presenting the tragedy of Quasimodo’s isolation alongside the hope found in his bond with Esmeralda, The Hunchback of Notre Dame encourages us to approach others with empathy and understanding—a timeless lesson that echoes across generations.

Directorial Choices and Cinematic Techniques

Wallace Worsley’s direction in The Hunchback of Notre Dame brought a sophisticated approach to silent film, using the medium’s visual language to shape the film’s mood and emotional impact. Worsley’s command of lighting, shadows, and camera angles adds a dramatic depth to the film, highlighting Quasimodo’s inner turmoil and the oppressive, Gothic atmosphere of medieval Paris. Through his directing style, Worsley brings to life a world where light and dark are in constant tension, symbolizing the struggle between compassion and cruelty that lies at the heart of the story.

Several key scenes showcase Worsley’s skill in using visual storytelling to heighten emotional intensity. One of the most powerful sequences is Quasimodo’s public torture, where he is bound, whipped, and humiliated in the town square. In this scene, Worsley combines close-ups of Quasimodo’s agonized face with wide shots of the jeering crowd, amplifying the sense of isolation and injustice. The close-ups reveal Chaney’s expressive performance, allowing the audience to feel Quasimodo’s pain and humiliation with visceral immediacy. Worsley also makes powerful use of Notre Dame’s bell tower, where the towering height and shadowed recesses serve as both refuge and prison for Quasimodo. The sequences in the bell tower, with sweeping views of Paris and claustrophobic close-ups within the cathedral’s recesses, capture both the majesty and confinement that define Quasimodo’s existence.

Worsley’s reliance on silent film techniques to convey emotion and tension is nothing short of masterful. In an era before sound, every glance, gesture, and shadow had to carry weight, and The Hunchback of Notre Dame exemplifies this skill. Worsley uses light and shadow to portray Quasimodo’s complex emotions—loneliness, desperation, and fleeting joy—without the need for dialogue. In place of words, the camera lingers on moments of pain or tenderness, allowing the audience to interpret the characters’ thoughts and feelings through visual cues alone. This reliance on visual expression, essential to silent cinema, amplifies the film’s emotional resonance and creates a heightened experience that draws the audience directly into Quasimodo’s world.

Through these cinematic choices, Worsley transforms The Hunchback of Notre Dame into a haunting, visually expressive experience. His direction is a testament to the power of silent film, proving that even without spoken words, a story of this magnitude can move audiences, conveying the full spectrum of human emotion in a language of light, shadow, and movement.