Table of Contents

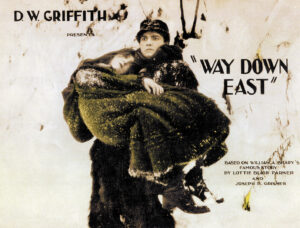

“Way Down East,” a 1920 silent film directed by the legendary D.W. Griffith, stands as a testament to the enduring power of early cinema. This film, an adaptation of Lottie Blair Parker’s popular play, delves deep into themes of morality, social justice, and personal redemption. Set against the backdrop of rural New England, the movie tells the story of Anna Moore, a young woman who faces societal scorn and personal tragedy before finding love and acceptance. Griffith, known for his groundbreaking work in cinema, brings his trademark storytelling techniques and emotional depth to this classic narrative, making “Way Down East” a compelling watch even a century after its release.

D.W. Griffith, often hailed as one of the most influential directors in the history of cinema, had a profound impact on the development of film as an art form. His innovative use of narrative structure, cross-cutting, and close-ups revolutionized the way stories were told on screen. “Way Down East” showcases Griffith’s ability to blend melodrama with social commentary, creating a film that is both entertaining and thought-provoking. The movie’s exploration of issues such as gender inequality and class disparities resonates with audiences, highlighting Griffith’s knack for weaving complex themes into engaging plots. Through its rich narrative and innovative techniques, “Way Down East” remains a significant piece in the tapestry of early American cinema.

Released in 1920, “Way Down East” came at a time when the silent film era was in full swing, and Hollywood was cementing its place as the epicenter of the film industry. This period was marked by significant technological advancements and a burgeoning audience eager for new and captivating stories. The film was based on the popular 1897 play by Lottie Blair Parker, which had already enjoyed a successful run on stage. By adapting this well-known play, D.W. Griffith was able to draw upon an existing fan base while also reaching new audiences through the cinematic medium. The film’s moral and social themes resonated deeply with the post-World War I audience, who were navigating a rapidly changing social landscape.

The movie’s production was ambitious for its time, both in scale and budget. With an estimated budget of around $700,000—a substantial amount in the early 1920s—Griffith spared no expense in bringing the story to life. Filming took place in various locations, including the Mamaroneck Studios in New York and the Connecticut River, where the famous ice floe sequence was shot under perilous conditions. This sequence, in particular, highlighted Griffith’s dedication to realism and his willingness to push the boundaries of film production. The combination of indoor and outdoor locations, along with the use of real snow and ice, contributed to the film’s authenticity and visual impact, making “Way Down East” a landmark achievement in silent cinema.

“Way Down East” centers on the trials and tribulations of Anna Moore, a young woman from a modest background who is sent to the city by her mother to seek financial help from wealthy relatives. In the city, Anna encounters Lennox Sanderson, a wealthy and unscrupulous playboy who deceives her into a sham marriage. After discovering the truth and being left abandoned and pregnant, Anna faces severe societal condemnation and is forced to seek refuge in the countryside. This pivotal deception and its repercussions set the stage for a story rich in drama and moral conflict, highlighting the harsh realities faced by women of that era.

The heart of the film lies in its characters, particularly Anna Moore, portrayed with poignant vulnerability by Lillian Gish. Anna embodies innocence and resilience, enduring immense hardship yet retaining her dignity. Her journey intersects with David Bartlett, played by Richard Barthelmess, a kind and honorable young farmer. David’s character provides a stark contrast to the deceitful Lennox Sanderson, played by Lowell Sherman, who epitomizes the moral decay of the urban elite. The chemistry between Anna and David grows throughout the film, offering a glimmer of hope and love amidst Anna’s turmoil.

Several key events drive the narrative forward, intensifying the emotional stakes. After being deceived and abandoned by Lennox, Anna gives birth to a child who tragically dies, further deepening her despair. Seeking anonymity, she finds work at the Bartlett farm, where she gradually earns the affection and respect of the Bartlett family, particularly David. The climax of the film is marked by the iconic ice floe sequence, where Anna, pursued by the villainous Lennox, is swept onto a drifting ice floe on a river. David’s daring rescue of Anna from the perilous ice floe cements his heroism and their bond. This sequence not only showcases Griffith’s technical prowess but also serves as a powerful metaphor for Anna’s tumultuous journey and eventual salvation.

D.W. Griffith’s direction exemplifies his mastery of storytelling and cinematic innovation. Known for his ability to elicit deep emotional responses, Griffith carefully crafts each scene to enhance the narrative’s dramatic impact. His use of close-ups to capture the subtle nuances of Lillian Gish’s performance as Anna Moore allows the audience to connect intimately with her character’s plight. Griffith’s pacing is deliberate, allowing the story to unfold naturally while maintaining a strong emotional undercurrent. His attention to detail and ability to weave complex social themes into a cohesive narrative demonstrate his skill as a storyteller and director.

Griffith’s use of camera work and editing in “Way Down East” was groundbreaking for its time. He employed dynamic camera movements and innovative editing techniques to heighten the film’s dramatic tension. Cross-cutting, a technique Griffith popularized, is used effectively to build suspense, particularly during the film’s climax. The seamless transitions between indoor and outdoor scenes create a sense of realism and continuity, drawing the audience deeper into the story. Griffith’s strategic use of lighting and composition further enhances the film’s visual appeal, making “Way Down East” a visually compelling work of art.

One of the most notable scenes is the iconic ice floe sequence, a testament to Griffith’s technical ingenuity and dedication to realism. Filmed on location in the frigid Connecticut River, this scene features Anna Moore stranded on a drifting ice floe, with the river’s icy waters threatening to engulf her. The use of real ice and water, combined with Gish’s harrowing performance, creates a palpable sense of danger and urgency. Griffith’s decision to shoot this sequence under such perilous conditions demonstrates his commitment to authenticity. The meticulous editing and camera angles used to capture the rescue sequence by David Bartlett heighten the scene’s dramatic intensity, making it one of the most memorable and technically impressive moments in silent cinema history.

“Way Down East,” while celebrated for its technical achievements and emotional depth, was not without its criticisms and controversies. Contemporary critics praised the film’s storytelling and Griffith’s direction, but some took issue with its melodramatic elements, considering them excessive and manipulative. Modern critics have also pointed out the film’s reliance on Victorian moralism, which can feel dated and overly moralistic to contemporary audiences. Despite these critiques, the film’s ability to evoke strong emotional reactions and its ambitious production values have largely overshadowed its perceived flaws.

One of the main controversies relates to D.W. Griffith himself. Griffith was a pioneering figure in early cinema, but his legacy is marred by his earlier work, “The Birth of a Nation” (1915), which is infamous for its racist portrayals and glorification of the Ku Klux Klan. This earlier film casts a long shadow over his subsequent work, including “Way Down East.” Critics and scholars often grapple with separating Griffith’s technical and narrative contributions to cinema from the problematic themes he propagated in his earlier films. This duality in Griffith’s legacy complicates the reception of “Way Down East,” as audiences and critics are reminded of the broader context of his filmography.

Additionally, the film faced scrutiny for its portrayal of gender roles and social class. The film’s depiction of Anna Moore’s suffering and eventual redemption through traditional gender roles reflects the prevailing attitudes of its time. Some modern viewers find the film’s treatment of Anna’s character to be overly simplistic and rooted in outdated notions of femininity and virtue. Furthermore, the stark contrast between the moral purity of rural life and the corrupting influence of urban environments can be seen as a simplistic and romanticized view of society. These aspects of the film continue to spark debate among film historians and critics, who analyze how “Way Down East” both reflects and challenges the cultural norms of its era.

“Way Down East” remains a powerful example of early American cinema, showcasing both the strengths and weaknesses of its time. Its strengths lie in the compelling performances, particularly by Lillian Gish, and the innovative cinematic techniques employed by D.W. Griffith. The film’s dramatic storytelling, emotional depth, and technical achievements, such as the iconic ice floe sequence, highlight Griffith’s visionary approach to filmmaking. However, the film’s reliance on melodrama and Victorian moralism, along with its portrayal of gender roles and social class, can feel outdated to modern audiences.

Despite these criticisms, “Way Down East” holds a significant place in film history. It exemplifies the evolution of narrative cinema and Griffith’s influential role in shaping the medium. The film’s exploration of themes like morality, redemption, and societal judgment continues to resonate, offering valuable insights into the cultural and social dynamics of the early 20th century. For contemporary viewers, it provides a fascinating glimpse into the silent film era’s artistry and storytelling capabilities.