Table of Contents

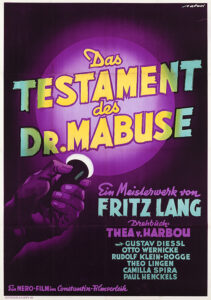

Fritz Lang’s “The Testament of Dr. Mabuse” (1933) picks up where its predecessor left off, diving back into the twisted world of the criminal mastermind Dr. Mabuse. Last week I reviewed “Dr. Mabuse the Gambler” (1922); this week we’re reviewing the sequel where, eleven years later, Lang brings Mabuse back to the screen, this time with a crackling soundtrack to accompany the madness.

This sequel comes at a fascinating point in Lang’s career. It’s one of his last German films before he packed his bags for Hollywood, and you can feel the tension of 1930s Germany seeping into every frame. But what really sets this film apart is how Lang tackles the new challenge of sound.

When talkies first hit the scene they were very much akin to a recorded stage play, something which Lang would not be content with; instead, he uses sound like a maestro, weaving it into his visual storytelling in ways that’ll make you forget silent films were ever a thing. Creaking doors, disembodied voices, and the relentless tick of a clock all keep you on the edge of your seat.

Lang’s use of sound is nothing short of revolutionary for its time. He doesn’t just add dialogue and call it a day; instead, he crafts a rich soundscape that becomes an integral part of the storytelling. The film opens with a cacophony of industrial noise – a rhythmic, mechanical pounding that immediately sets your teeth on edge. This isn’t just background noise; it’s a character in itself, building tension and reflecting the psychological state of the characters.

But it’s not all about the noise. Lang knows the power of silence too. He uses sudden drops in sound to startling effect, creating moments of eerie quiet that are just as impactful as the loudest explosion. This masterful control of audio dynamics keeps the audience constantly on edge, never knowing what auditory surprise might come next.

Visually, Lang hasn’t lost a step in the transition to sound. His cinematography retains all the shadowy expressionism of his silent work, with stark contrasts and unsettling angles that would make any film noir director green with envy. The camera moves with purpose and every light and shadow is purposefully placed.

Special effects in “The Testament of Dr. Mabuse” are subtle by today’s standards but innovative for their time. Lang uses superimposition to chilling effect, creating ghostly apparitions that blur the line between reality and madness. In one particularly striking scene, the spectral image of Dr. Mabuse appears to grow larger, dominating the frame in a visual representation of his overwhelming influence.

Perhaps the most impressive technical feat is how Lang seamlessly integrates these various elements. Sound, visuals, and special effects don’t just coexist; they enhance each other. A creaking door isn’t just a sound effect; it’s paired with a slowly widening shot that ratchets up the suspense. The superimposed image of Mabuse is accompanied by an otherworldly voice, creating a multi-sensory experience of the uncanny.

In an era when many filmmakers were still finding their footing with sound, Lang was already pushing the boundaries of what was possible. “The Testament of Dr. Mabuse” stands as a testament not just to its eponymous character, but to Lang’s innovative spirit and technical mastery. It’s a film that doesn’t just use sound – it harnesses it, shapes it, and turns it into an art form all its own.

Overview

“The Testament of Dr. Mabuse” plunges us into a Berlin gripped by a crime wave of near-mythic proportions. As the city reels from a series of seemingly unconnected criminal acts, we’re introduced to our principal characters: Inspector Lohmann, a dogged detective determined to crack the case, and Dr. Baum, the psychiatrist in charge of the mental institution where the infamous Dr. Mabuse now resides.

The twist? Mabuse, once a criminal mastermind of unparalleled genius, is now catatonic, spending his days scribbling indecipherable notes that only Dr. Baum can decipher. As Lohmann investigates the crime spree, he begins to uncover an unsettling pattern – the crimes bear an eerie resemblance to plans outlined in Mabuse’s writings. What follows is a labyrinthine plot that weaves together multiple storylines. We follow Lohmann’s investigation, the plight of a reformed criminal drawn back into the underworld, and Dr. Baum’s growing obsession with Mabuse’s writings. All the while, the specter of Mabuse looms large, his influence seemingly undiminished despite his physical incapacitation.

Without venturing into spoiler territory, let’s just say that the line between sanity and madness, reality and illusion, becomes increasingly blurred as the film hurtles towards its explosive climax.

Thematically, “The Testament of Dr. Mabuse” is a rich tapestry that explores several interconnected ideas:

- Mind Control and Influence: The film delves deep into the concept of one mind dominating another, whether through hypnosis, persuasion, or sheer force of will. Mabuse’s ability to control others, even from his hospital bed, raises unsettling questions about the nature of free will and the power of suggestion.

- The Nature of Criminality: Lang presents crime not just as individual acts, but as an organized, almost corporate entity. The film explores the idea of crime as a philosophy, a system that can outlive any individual criminal.

- Power and Its Corruption: The pursuit and exercise of power is a central theme. We see how the promise of power can corrupt even seemingly upright individuals, and how absolute power can lead to absolute madness.

- Identity and Duality: Many characters in the film struggle with dual natures or identities, reflecting a larger theme about the multiplicity of the self.

- Technology and Modernity: Set against the backdrop of 1930s Berlin, the film also touches on anxieties about modern urban life and the double-edged nature of technological progress.

Underlying all of these themes is a palpable sense of unease about the future. Made on the cusp of Nazi Germany’s rise to power, “The Testament of Dr. Mabuse” can be read as an allegory for the seductive and destructive nature of totalitarian ideologies.

Lang weaves these complex themes into a taut thriller framework, creating a film that works both as a gripping crime story and a deeper meditation on power, control, and the darker aspects of human nature.

Characters and Performances

The return of Dr. Mabuse to the silver screen is a study in character evolution and acting prowess. While the 1922 film gave us Rudolf Klein-Rogge’s mesmerizing portrayal of Mabuse as a physically present, dynamic villain, this sequel presents us with a Mabuse who is somehow more terrifying in his absence.

Klein-Rogge reprises his role, but in a radically different form. His Mabuse is now a near-catatonic patient, seen primarily in fleeting glimpses and flashbacks. Yet, even in this diminished state, Klein-Rogge manages to convey the character’s malevolent power. His piercing gaze and rigid posture suggest a mind still churning with dark schemes, despite his body’s immobility. It’s a masterclass in doing more with less, proving that Klein-Rogge’s command of the character transcends physical action.

The void left by Mabuse’s physical absence is filled by Dr. Baum, brilliantly portrayed by Oscar Beregi Sr. Baum’s descent from respected psychiatrist to Mabuse’s de facto successor is one of the film’s most compelling arcs. Beregi plays this transformation with chilling subtlety, slowly peeling back layers of professional detachment to reveal a man consumed by the very madness he sought to study. His final scene, which I won’t spoil here, is a tour de force that rivals Klein-Rogge’s best moments from the original film.

Otto Wernicke returns as Inspector Lohmann, a character he first played in Lang’s “M” (1931). Wernicke’s Lohmann is a gruff, no-nonsense detective who serves as the audience’s anchor in this world of shadowy criminals and fragile psyches. His dogged pursuit of the truth provides a counterpoint to the film’s more fantastical elements, and Wernicke plays him with a world-weary charm that’s impossible not to root for.

Gustav Diessl as Thomas Kent, a reformed criminal drawn back into the underworld, delivers a performance fraught with inner conflict. Diessl masterfully portrays a man walking a tightrope between his desire for redemption and the inexorable pull of his criminal past. His scenes with Wera Liessem, who plays his love interest Lilli, crackle with a tension born of genuine chemistry and the looming threat of Kent’s criminal entanglements.

When compared to the 1922 film, “The Testament of Dr. Mabuse” presents a more ensemble-driven narrative. While the original centered largely on Mabuse himself, this sequel distributes the dramatic weight across a wider cast of characters. This shift allows for a richer, more complex exploration of Mabuse’s influence, showing how his ideology infects and transforms those around him.

The performances in this film also reflect the transition from silent to sound cinema. Gone are the exaggerated gestures and expressions necessary in silent film. Instead, we see a more naturalistic style of acting, with the actors using their voices as much as their bodies to convey emotion and intent. This is particularly evident in the scenes of confrontation and interrogation, where the power of a whispered threat or a sharply intoned question adds layers of meaning that silent film could only imply.

Despite these changes, there’s a clear throughline in the portrayal of madness and obsession from the 1922 film to this sequel. The intensity that Klein-Rogge brought to the original Mabuse is echoed and amplified in Beregi’s portrayal of Baum. Both performances center on the eyes – windows to the soul twisted by megalomaniacal delusions.

In crafting these layered performances, Lang and his cast create a world where the line between sanity and madness is ever-shifting, and the real threat isn’t just one man, but an idea that can possess anyone. It’s a chilling concept, brought to life by a ensemble that understood the power of subtlety in the new era of sound film.

Director’s Vision

Fritz Lang’s approach to “The Testament of Dr. Mabuse” reveals a filmmaker at the height of his powers, unafraid to push the boundaries of cinema while grappling with the tumultuous sociopolitical climate of his time.

In crafting this sequel, Lang doesn’t simply rehash the formula that made the original “Dr. Mabuse” a success. Instead, he uses the familiar character as a springboard to explore new cinematic territories. The shift from silent to sound film is not just a technical challenge for Lang; it’s an opportunity to redefine the language of thriller cinema.

Lang’s vision for the sequel is more abstract and psychological than its predecessor. While the 1922 film presented Mabuse as a tangible threat, here he becomes an almost mythical figure, an idea more than a man. This approach allows Lang to delve deeper into themes of power, control, and the nature of evil itself.

The political and social commentary in “The Testament of Dr. Mabuse” is impossible to ignore, especially given the historical context of its release. Made as the Nazi party was rising to power in Germany, the film can be read as a chilling allegory for the spread of totalitarian ideologies. Mabuse’s criminal empire, with its blind obedience to an unseen leader and its goal of creating a “Empire of Crime,” bears unsettling similarities to the political realities of the time. Lang himself stated that he used Mabuse’s words to paraphrase Nazi slogans and ideology. This bold move led to the film being banned by the Nazi regime shortly after its release. The character of Dr. Baum, a respected professional who falls under the sway of a destructive ideology, can be seen as a representation of how seemingly rational individuals can be seduced by extremist ideas.

Beyond its political dimensions, the film also comments on the nature of modernity itself. The urban setting, with its web of criminals exploiting technology for nefarious purposes, reflects anxieties about the dark side of progress and the alienation of city life.

Historical Context

To fully appreciate “The Testament of Dr. Mabuse,” we need to understand the tumultuous historical backdrop against which it was created. The film was produced and released during one of the most pivotal moments in 20th-century history: the rise of the Nazi regime in Germany.

Fritz Lang completed “The Testament of Dr. Mabuse” in early 1933, just as Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor of Germany. This was a time of immense political upheaval, with the Weimar Republic crumbling and the Nazi Party consolidating its power. The parallels between the film’s portrayal of a criminal empire built on fear and manipulation and the real-world political situation were impossible to ignore. Lang, with his astute political awareness, didn’t shy away from these parallels. In fact, he later claimed that he had used the character of Dr. Mabuse to voice actual Nazi party slogans and ideology, thinly veiled as the ramblings of a madman. This was a bold and dangerous artistic choice, effectively turning the film into a critique of the rising totalitarian regime.

The film’s reception in this charged atmosphere was mixed and ultimately short-lived. While it was passed by the censorship board and had a successful premiere in Budapest, its fate in Germany was sealed. Joseph Goebbels, the newly appointed Minister of Propaganda, quickly recognized the film’s subversive potential. He banned “The Testament of Dr. Mabuse” on the grounds that it could weaken the public’s trust in its leaders. This banning marked a turning point not just for the film, but for Lang himself. In a famous (though possibly embellished) account, Lang claimed that Goebbels summoned him for a meeting, praising his filmmaking skills and offering him a position as head of the German film industry. Instead of accepting, Lang fled Germany that very night, leaving behind his money and many of his possessions. While the exact details of this story are disputed, what’s certain is that Lang left Germany for Paris shortly after, eventually making his way to Hollywood.

Film noir, which would emerge in the 1940s, owes a significant debt to Lang’s work in general and “The Testament of Dr. Mabuse” in particular. The film’s shadowy visual style, its theme of a society permeated by crime, and its morally ambiguous characters all anticipate key noir elements. Moreover, the film’s depiction of a criminal mastermind operating from behind the scenes influenced countless future thrillers. From James Bond villains to the nameless conspiracies of paranoid 1970s thrillers, the shadow of Mabuse looms large.

The film’s exploration of the thin line between sanity and madness, and its use of psychological manipulation as a plot device, also presaged later psychological thrillers. Works like “Silence of the Lambs” or “Se7en,” with their brilliant, incarcerated villains, can trace a lineage back to Lang’s Mabuse. In a broader sense, “The Testament of Dr. Mabuse” stands as a testament to the power of film as a medium for social and political commentary. It demonstrates how genre cinema can be used to engage with urgent real-world issues, a tradition that continues in socially conscious thrillers to this day.

By intertwining its fictional narrative so closely with its historical moment, “The Testament of Dr. Mabuse” transcended its status as mere entertainment. It became a historical document in its own right, capturing the anxiety and resistance of artists living under the shadow of totalitarianism. In doing so, it set a standard for politically engaged genre filmmaking that remains relevant and influential to this day.

Sound Design and Music

The transition from silent to sound film was a seismic shift in cinema history, and “The Testament of Dr. Mabuse” stands as a testament to Fritz Lang’s mastery of this new medium. Rather than simply adding dialogue to a visual narrative, Lang fully embraced the possibilities of sound, using it as an integral storytelling tool. From the film’s opening sequence, it’s clear that sound is not merely an addition, but a crucial element of the narrative. The rhythmic, mechanical pounding that accompanies the opening credits immediately creates a sense of unease and tension. This isn’t just background noise; it’s a character in itself, setting the tone for the entire film.

Lang’s use of diegetic sound (sounds whose source is visible on screen or implied to be present by the action) is particularly noteworthy. The creaking of doors, the ticking of clocks, the rustling of papers – all these everyday sounds are amplified and used to heighten tension. In one particularly effective scene, the simple sound of water dripping becomes an almost unbearable source of psychological torment.

But it’s in his use of non-diegetic sound (sound whose source is neither visible on screen nor implied to be present in the action) that Lang truly shines. Disembodied voices, seemingly emanating from nowhere, add to the film’s unsettling atmosphere. These voices, often representing Mabuse’s influence, blur the line between reality and hallucination, leaving both the characters and the audience questioning what’s real.

The film’s approach to dialogue is equally innovative. Lang doesn’t fall into the trap of many early talkies, which often became stagey and static in their attempt to capture clear dialogue. Instead, he allows for overlapping conversations, distant shouts, and even moments of unintelligibility. This naturalistic approach to dialogue adds to the film’s sense of realism while also contributing to its overall soundscape.

Music in “The Testament of Dr. Mabuse” is used sparingly but effectively. Unlike many films of the era, which relied heavily on musical scores to guide audience emotions, Lang often opts for silence or ambient sound. When music is used, it’s often to heighten moments of tension or to signify the presence of Mabuse’s influence. This restrained approach to scoring allows the other sound elements to take center stage.

Conversely, one of the most striking aspects of the film’s sound design is its use of silence. In a medium that had just gained the ability to talk, Lang understood the power of withholding sound. Sudden drops into silence are used to great effect, creating moments of eerie quiet that are just as impactful as the loudest explosion.

The film also experiments with sound perspective, adjusting volume and clarity to match the visual perspective of shots. This technique, revolutionary for its time, adds depth to the soundscape and enhances the viewer’s sense of space within the film. Lang’s innovative use of sound in “The Testament of Dr. Mabuse” had a profound influence on the development of cinema audio. His techniques for creating atmosphere, building tension, and enhancing narrative through sound laid the groundwork for generations of filmmakers to come. From film noir to modern psychological thrillers, the echoes of Lang’s auditory innovations can still be heard today.

In many ways, “The Testament of Dr. Mabuse” serves as a masterclass in the potential of sound in cinema. It demonstrates how audio can be used not just to complement the visual elements of a film, but to expand its narrative possibilities, deepen its themes, and intensify its emotional impact. Lang’s work here set a new standard for sound design in film, one that continues to influence filmmakers to this day.

For vintage film enthusiasts, “The Testament of Dr. Mabuse” is an essential watch. Here are a few recommendations for approaching and appreciating this classic:

- Context is Key: Familiarize yourself with the historical context of the film’s production. Understanding the political climate of 1933 Germany will greatly enhance your appreciation of Lang’s subversive message.

- Pay Attention to Sound: Given the film’s innovative use of sound, watch it in the best audio setting you can. Pay particular attention to how Lang uses sound to create atmosphere and drive the narrative.

- Watch the Precursor: If possible, watch “Dr. Mabuse the Gambler” (1922) before this film. While not strictly necessary, it will give you a fuller appreciation of how Lang evolved the character and his techniques.

- Engage with the Themes: Don’t just focus on the surface-level thriller aspects. Engage with the deeper themes of power, control, and the nature of evil. These elements elevate the film from mere entertainment to a work of lasting significance.

- Explore Its Legacy: After watching, consider exploring some of the films influenced by “The Testament of Dr. Mabuse.” From film noir to modern psychological thrillers, its impact can be felt across decades of cinema.

“The Testament of Dr. Mabuse” is more than just a well-preserved relic of cinema history. It’s a film that continues to resonate, challenge, and inspire. Its technical innovations, narrative complexity, and political courage make it a must-see for anyone interested in the power and potential of cinema. As we face our own uncertain times, Lang’s final German film remains a potent reminder of the artist’s role in society and the enduring power of a well-told story.