Table of Contents

A Silent Masterpiece of Crime and Control

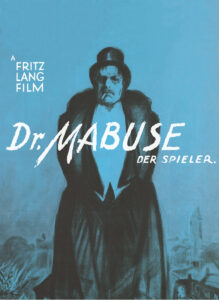

Fritz Lang’s “Dr. Mabuse the Gambler” (1922) stands as a towering achievement in the annals of silent cinema. This German expressionist epic, spanning nearly four and a half hours, weaves a complex tapestry of crime, manipulation, and societal decay that continues to captivate audiences a century after its release.

At its core, the film introduces us to Dr. Mabuse, a criminal mastermind whose ability to control minds and orchestrate elaborate schemes makes him one of cinema’s earliest and most compelling villains. Lang’s ambitious work not only serves as a thrilling crime drama but also as a prescient commentary on the fragility of social order and the seductive nature of power.

Released in two parts – “The Great Gambler” and “Inferno” – the film showcases Lang’s innovative storytelling techniques and visual style, which would later influence countless filmmakers across genres. As we delve into this silent classic, we’ll explore how “Dr. Mabuse the Gambler” set new standards for narrative complexity in cinema and why it remains a crucial work for film enthusiasts and historians alike.

Fritz Lang, the visionary behind “Dr. Mabuse the Gambler,” was already a rising star in German cinema when he embarked on this ambitious project. Born in Vienna in 1890, Lang had initially pursued a career in architecture before finding his true calling in filmmaking. His meticulous attention to visual detail and structural narrative complexity, evident in earlier works like “Der Müde Tod” (1921), reached new heights with the Mabuse saga. Lang’s experience in the Austrian army during World War I and his witnessing of the socio-political upheaval in post-war Germany significantly influenced his artistic vision, infusing his films with a palpable sense of unease and skepticism towards authority.

The release of “Dr. Mabuse the Gambler” in 1922 coincided with a tumultuous period in German history. The Weimar Republic, established after World War I, was grappling with severe economic instability, political extremism, and social disillusionment. Hyperinflation was rampant, and the national psyche was still reeling from the humiliation of defeat. Against this backdrop, Lang’s film struck a chord with audiences who saw in Dr. Mabuse a reflection of the chaotic forces threatening to unravel their society. The character’s ability to manipulate markets and minds alike resonated deeply in a nation where trust in institutions was at an all-time low. Moreover, the film’s release marked a high point in the golden age of German expressionist cinema, a movement characterized by its emphasis on psychological complexity and visual distortion to convey emotional states.

“Dr. Mabuse the Gambler” unfolds in two distinct parts, each offering a deep dive into the machinations of its titular character. Part 1, “The Great Gambler,” introduces us to Dr. Mabuse (played with chilling intensity by Rudolf Klein-Rogge), a criminal mastermind who uses hypnosis, disguise, and manipulation to control Berlin’s underworld. We follow Mabuse as he orchestrates elaborate schemes to manipulate the stock market, cheat at gambling, and amass both wealth and power. His methods are as diverse as they are devious – from using telepathic abilities to influence card games to employing a network of spies and collaborators to gather sensitive information. The film meticulously details Mabuse’s operations, showing how he exploits the weaknesses of a society still reeling from the aftermath of World War I. His path crosses with that of the young millionaire Edgar Hull, whom Mabuse hypnotizes and swindles in a high-stakes poker game, and Countess Told, whose husband becomes another of Mabuse’s victims through manipulated stock trades. As State Prosecutor Norbert von Wenk begins to investigate the strange occurrences surrounding these events, he finds himself drawn into a dangerous cat-and-mouse game with the elusive Mabuse. The prosecutor’s efforts to unravel the mystery lead him through Berlin’s seedy underbelly, from opulent gambling dens to shadowy criminal hideouts, all the while unaware that Mabuse is always one step ahead, often hiding in plain sight through his mastery of disguise.

Part 2, aptly titled “Inferno,” sees the noose tightening around Mabuse as von Wenk closes in on his criminal empire. The narrative takes on a more frenetic pace, with Mabuse’s carefully constructed world beginning to crumble under the weight of his own ambition and the relentless pursuit of justice. He kidnaps Countess Told, leading to a tense standoff with the authorities that showcases Lang’s skill in building suspense through innovative camera work and editing techniques. As his allies are picked off one by one and his schemes unravel, Mabuse descends into paranoia and madness, a psychological breakdown portrayed with haunting effectiveness by Klein-Rogge. The film culminates in a spectacular sequence where Mabuse, holed up in his counterfeiting headquarters, faces hallucinations of his victims and the ghosts of his crimes. These visions, brought to life through pioneering special effects, serve as a surreal and nightmarish reflection of Mabuse’s fractured psyche. The final confrontation between Mabuse and the forces of law and order serves as a powerful denouement to this epic tale of crime and punishment, with Lang using the clash to comment on the eternal struggle between chaos and order in society. As Mabuse’s empire falls, the film leaves viewers to ponder the lasting impact of his actions and the potential for other Mabuse-like figures to rise in times of social upheaval.

The cinematography in “Dr. Mabuse the Gambler” is a testament to Fritz Lang’s innovative visual style and the broader aesthetics of German Expressionism. Cinematographer Carl Hoffmann, working closely with Lang, employs a range of techniques to create a world of stark contrasts and unsettling perspectives. The film makes extensive use of chiaroscuro lighting, casting long, dramatic shadows that mirror the moral ambiguity of its characters. Dynamic camera movements, though limited by the technology of the time, are used to great effect, particularly in the gambling den scenes where the camera pans across faces, building tension and revealing subtle reactions. Close-ups are used sparingly but powerfully, often focusing on Mabuse’s piercing eyes to emphasize his hypnotic powers. The framing of shots is meticulously composed, with characters often positioned asymmetrically to create a sense of unease and imbalance, reflecting the destabilized society depicted in the film.

The set design of “Dr. Mabuse the Gambler” is a crucial element in creating the film’s distinctive atmosphere, seamlessly blending realism with expressionistic elements. Art directors Otto Hunte and Karl Vollbrecht crafted elaborate, detailed sets that bring to life the various locales of 1920s Berlin, from opulent Art Deco interiors of high-society gatherings to the grimy, claustrophobic backrooms of the criminal underworld. Mabuse’s lair, in particular, is a triumph of design, with its labyrinthine structure and hidden passages reflecting the character’s complex and secretive nature. The sets often feature distorted geometries and exaggerated proportions, characteristic of the German Expressionist movement, which serve to externalize the psychological states of the characters. This is particularly evident in the later scenes of Mabuse’s breakdown, where the set design becomes increasingly abstract and nightmarish, mirroring his descent into madness.

While “Dr. Mabuse the Gambler” predates many of the special effects techniques that would become standard in later films, it nonetheless showcases several innovative visual tricks that were groundbreaking for its time. The film’s most notable special effects are employed in the scenes depicting Mabuse’s hypnotic powers and the hallucinations experienced by his victims. These sequences use double exposures and superimpositions to create ghostly, translucent images that float across the screen, effectively conveying the otherworldly nature of Mabuse’s abilities. In one particularly striking scene, Mabuse’s disembodied eyes appear floating in darkness, a simple yet powerful effect that underscores his omnipresent threat. The film also makes use of miniatures and forced perspective in certain shots to create a sense of scale and grandeur beyond what could be achieved with full-size sets. While these effects may appear primitive by modern standards, they demonstrate Lang’s commitment to pushing the boundaries of visual storytelling and contribute significantly to the film’s enduring ability to captivate and unsettle audiences.

Power and manipulation are central themes in “Dr. Mabuse the Gambler,” embodied primarily through the titular character’s actions and influence. Mabuse’s ability to control others through hypnosis and deception serves as a metaphor for the seductive nature of power and the vulnerability of individuals to manipulation. The film explores how power can corrupt absolutely, with Mabuse’s increasing control over Berlin’s underworld paralleling his moral degradation.

Lang uses Mabuse’s criminal empire as a lens to examine the broader power structures in society, questioning the thin line between legitimate authority and criminal control. The ease with which Mabuse infiltrates and manipulates various social circles – from gambling dens to stock exchanges – highlights the pervasive nature of corruption and the potential for power to be wielded invisibly.

The film’s exploration of power extends to its visual language, with Mabuse often framed in dominant positions within shots, looming over his victims or puppet-like subordinates. This visual hierarchy reinforces the theme of power imbalance and the far-reaching consequences of unchecked authority.

“Dr. Mabuse the Gambler” offers a scathing commentary on the social and economic conditions of Weimar-era Germany. The film portrays a society in disarray, grappling with the aftermath of World War I and the ensuing economic crisis. Through Mabuse’s exploitation of this chaos, Lang critiques the instability and moral bankruptcy of the era.

The depiction of various social classes – from the decadent upper class to the desperate lower classes – allows Lang to examine how societal upheaval can blur moral boundaries. The film suggests that in times of crisis, the line between criminality and respectability becomes increasingly porous. Moreover, the movie serves as a warning about the dangers of unchecked capitalism and the potential for financial systems to be manipulated by those with power and knowledge. Mabuse’s schemes in the stock market and gambling scenes illustrate how easily economic systems can be exploited, foreshadowing real-world financial crises.

Psychological elements play a crucial role in “Dr. Mabuse the Gambler,” with the film delving deep into the minds of its characters, particularly Mabuse himself. The use of hypnosis as a plot device allows Lang to explore themes of consciousness, free will, and the power of suggestion.

The film’s expressionistic style, with its distorted sets and exaggerated shadows, can be seen as an externalization of the characters’ psychological states. This is particularly evident in the scenes depicting Mabuse’s eventual mental breakdown, where the line between reality and hallucination blurs. Lang also examines the psychology of addiction and compulsion through the gambling motif. The casino scenes, with their tense close-ups and feverish pacing, capture the psychological toll of gambling addiction, serving as a microcosm for the larger themes of risk and control that permeate the film.

Dr. Mabuse, portrayed with mesmerizing intensity by Rudolf Klein-Rogge, stands as one of cinema’s most compelling and complex villains. A master of disguise and manipulation, Mabuse embodies the archetype of the criminal mastermind, yet transcends it through the depth of his characterization. His genius is matched only by his ruthlessness, as he employs hypnosis, psychological manipulation, and sheer force of will to bend others to his desires. Mabuse’s character serves as a dark mirror to society, reflecting its worst impulses and vulnerabilities.

Throughout the film, we witness the evolution of Mabuse from a calculated criminal to a man consumed by his own power. His descent into madness in the latter part of the film is particularly striking, revealing the psychological toll of his lifelong deceptions. This transformation is masterfully portrayed by Klein-Rogge, whose nuanced performance captures both Mabuse’s charismatic allure and his inner turmoil.

Mabuse’s multifaceted nature – doctor, gambler, hypnotist, criminal – makes him a symbol of the fractured identity of post-war Germany. His ability to seamlessly move between social classes and adopt various personas speaks to the fluid and uncertain nature of identity in a society undergoing rapid change. The character of Dr. Mabuse would go on to influence numerous fictional villains, establishing a template for the intellectual antagonist whose greatest weapon is his mind.

While Dr. Mabuse dominates the narrative, the film features several other key characters who serve as foils to his machinations. State Prosecutor Norbert von Wenk, Mabuse’s primary antagonist, represents the forces of law and order. His dogged pursuit of Mabuse provides the moral counterweight to the criminal’s schemes. Von Wenk’s character arc, from initial bewilderment to determined pursuit, mirrors society’s gradual awakening to the threats posed by figures like Mabuse.

Countess Told and her husband, Count Told, serve as representatives of the aristocratic class and its vulnerability to Mabuse’s influence. The Countess, in particular, becomes a focal point of Mabuse’s desires, symbolizing both his ambition to conquer high society and his human weaknesses. Her resistance to his charms provides one of the few challenges to Mabuse’s seeming omnipotence.

Edgar Hull, the young millionaire who falls victim to Mabuse’s gambling scheme, embodies the naivety and excess of the era’s youth. His character serves to illustrate the destructive allure of the lifestyle Mabuse promotes and exploits. Through Hull, Lang comments on the moral decay affecting even the most privileged members of society.

These supporting characters, while less fully developed than Mabuse, play crucial roles in creating a rich tapestry of social interactions and conflicts. Their varying responses to Mabuse’s influence – from resistance to capitulation – provide a nuanced exploration of human nature in the face of overwhelming power and temptation.

Fritz Lang’s “Dr. Mabuse the Gambler” stands as a monumental achievement in early cinema, a work that continues to captivate and intrigue viewers a century after its initial release. This silent epic, with its complex narrative, innovative technical aspects, and profound thematic depth, offers far more than mere entertainment. It serves as a time capsule of Weimar-era Germany, a psychological thriller that probes the depths of human nature, and a prescient commentary on the corrupting influence of power.

At the heart of the film’s enduring appeal is the character of Dr. Mabuse himself, brilliantly portrayed by Rudolf Klein-Rogge. Mabuse embodies the anxieties and moral ambiguities of his time, serving as both a terrifying villain and a dark reflection of society’s worst impulses. Through Mabuse’s rise and fall, Lang crafts a narrative that is as much about the character’s internal psychological journey as it is about his external machinations.

The film’s technical mastery – from its expressionistic cinematography to its groundbreaking special effects – set new standards for visual storytelling in cinema. Lang’s meticulous attention to detail in set design and his innovative use of visual symbolism create a rich, immersive world that pulls viewers into the shadowy realm of Mabuse’s Berlin.

For modern viewers, “Dr. Mabuse the Gambler” offers a unique window into the past while raising questions that remain startlingly relevant today. Its exploration of manipulation, power, and societal decay resonates in an era grappling with issues of fake news, economic inequality, and the influence of charismatic but morally bankrupt leaders.

While its length and the conventions of silent cinema may present challenges to contemporary audiences, “Dr. Mabuse the Gambler” rewards patient viewers with its depth, complexity, and artistry. It stands not just as a classic of German Expressionism, but as a timeless exploration of human nature and society. For film enthusiasts, historians, and anyone interested in the power of cinema to reflect and shape our understanding of the world, Lang’s masterpiece remains an essential and unforgettable viewing experience.