Table of Contents

Introduction

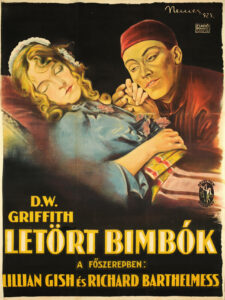

Released in 1919, Broken Blossoms takes us into the heart of London’s Limehouse district, where two fragile lives cross paths in a world that feels cold and unkind. Directed by D.W. Griffith, a pivotal figure in early cinema, this silent film stands out for its willingness to tackle difficult subjects like cultural isolation and domestic abuse—topics rarely touched upon in mainstream movies of the time. At the film’s center is Cheng Huan, a soft-spoken immigrant from China, and Lucy Burrows, a young girl struggling under the thumb of her abusive father. It’s a story about small moments of kindness amid cruelty, with characters whose lives speak to anyone who’s ever felt alone in a crowd.

Broken Blossoms isn’t without its complexities. Griffith’s portrayal of Cheng Huan reflects both sympathy and the racial stereotypes common in early 20th-century America, which can make the film a challenging watch for modern audiences. But it’s also a reminder of how powerful silent film could be—how, without a single spoken word, these characters and their stories continue to reach across time. Griffith’s use of moody lighting, close-ups, and understated performances creates an atmosphere that feels almost timeless, pulling us into a story that’s as visually striking as it is emotionally charged.

For those who love silent film or are curious about the early days of cinema, Broken Blossoms is a memorable journey. It may be a product of its era, but it’s also a testament to the emotional depth and storytelling that silent films were capable of bringing to life.

Plot Summary

In Broken Blossoms, we meet Cheng Huan, a gentle and idealistic young man who leaves his home in China, hoping to spread a message of peace in the bustling streets of London. But London’s Limehouse district, where he settles, is a harsh place, and his dreams slowly wither as he struggles to fit in. Across town, Lucy Burrows, a neglected young girl, endures a life of fear under the rule of her father, Battling Burrows, a violent prizefighter whose cruelty knows few bounds.

The story unfolds when fate brings Cheng Huan and Lucy together, leading to an unexpected friendship that offers each a brief respite from their bleak realities. In Cheng Huan, Lucy finds a kindness she’s never known, and in Lucy, Cheng Huan rediscovers a reason to care in a city that has largely dismissed him. But the peace they find together is fragile, threatened by forces beyond their control and the harsh prejudices of their world. It’s a story that dives into the depths of loneliness and the small moments of human connection that can offer hope—even if only for a little while.

Cinematic Techniques

Broken Blossoms is a silent film that relies heavily on visual storytelling, and Griffith’s cinematic approach draws the audience deep into the emotional world of its characters. One of the film’s most striking features is its use of lighting and shadow to create a moody, almost dreamlike atmosphere. Griffith employs chiaroscuro lighting, a technique borrowed from classic art, to contrast light and darkness within scenes. This helps convey the emotional states of Cheng Huan and Lucy without words—particularly in Lucy’s dim, cramped home, where shadows emphasize her isolation and fear.

Close-ups are also a defining feature in Broken Blossoms, used to great effect to draw viewers into intimate moments. Griffith was one of the first filmmakers to realize the power of the close-up, and here he uses it to capture every tremor of Lucy’s expression and the quiet sadness in Cheng Huan’s gaze. These close-ups make the characters’ emotions feel more immediate and raw, connecting us to their silent struggles.

In addition to lighting and framing, Griffith made use of symbolic props to deepen the story. For example, a Buddha statue in Cheng Huan’s room represents his sense of peace and compassion—qualities that define his character and motivate his actions. This subtle symbol enriches his character and contrasts sharply with the violent world he’s entered. Griffith also makes creative use of set design, crafting the Limehouse district as an oppressive, gritty space that reflects the harsh lives of its residents. Through cramped rooms and cluttered streets, we feel the confinement and bleakness of the characters’ surroundings.

With these techniques, Broken Blossoms achieves a depth of storytelling that feels advanced for 1919. Griffith’s skill in capturing atmosphere and emotional subtlety helps the film overcome the limitations of silent cinema.

Themes and Social Commentary

Broken Blossoms isn’t just a silent drama; it’s a film that dives deep into the cultural and social issues of its time, touching on themes that still resonate today. At its core, the film explores loneliness and the search for human connection. Both Cheng Huan and Lucy live on the fringes of society, each isolated in their own way—Cheng by his immigrant status and the prejudices he faces, and Lucy by her abusive father. Their brief connection becomes a rare moment of kindness in a world that often feels indifferent, if not outright hostile.

One of the film’s central themes is the cultural divide between East and West. Griffith, to his credit, presents Cheng Huan as a gentle and spiritual man, in stark contrast to the rougher, often cruel English society around him. Yet, his portrayal is also complicated by the stereotypes of the era, with Cheng seen as the “other,” a figure of mystery and misunderstanding in London’s gritty Limehouse district. This dual portrayal reflects both Griffith’s attempt at a sympathetic character and the limitations of early 20th-century cultural depictions.

Domestic abuse and gender roles are also key themes in Broken Blossoms. Lucy’s father, Battling Burrows, is a violent man who sees Lucy as little more than a burden. His treatment of her—marked by cruelty and control—reveals the power dynamics and lack of protection for vulnerable women at the time. Lucy’s quiet resilience and suffering turn her into a symbol of innocence crushed by the unforgiving nature of her surroundings. In this way, the film shines a light on the often-ignored issue of domestic violence, portraying it with an honesty that was rare for its time.

Finally, Broken Blossoms speaks to the theme of idealism versus harsh reality. Cheng Huan arrives in London with dreams of spreading peace and kindness, but his vision quickly fades as he encounters a city closed off by prejudice and cruelty. Lucy, too, experiences a fleeting glimpse of kindness through her friendship with Cheng, but it’s a fragile respite. This clash between idealized compassion and the reality of human suffering gives the film a tragic depth, making its conclusion feel almost inevitable.

Performances and Impact

The heart of Broken Blossoms lies in its performances, especially from Lillian Gish, Richard Barthelmess, and Donald Crisp, whose portrayals bring a raw intensity to this silent-era classic. Lillian Gish, a frequent collaborator of Griffith’s, gives one of her most memorable performances as Lucy. With no dialogue to rely on, Gish uses her expressive face, fragile movements, and delicate body language to convey Lucy’s inner world—her fear, her brief moments of happiness, and her constant vulnerability. Her portrayal of Lucy as a young girl facing unimaginable hardships left a strong impression on audiences and helped define her as one of silent cinema’s first true stars.

Richard Barthelmess brings a quiet dignity to the role of Cheng Huan, imbuing his character with a gentle sadness and restrained emotion that reflect both his isolation and his compassion. Barthelmess’s Cheng Huan is a man who lives with sorrow and a deep empathy, which contrasts with the rough world around him. His subtle performance invites viewers to see past the cultural stereotypes of the time and recognize the character’s humanity. Barthelmess’s ability to balance Cheng Huan’s inner struggles and hopefulness adds depth to the film, earning him recognition as one of the silent era’s most talented actors.

Donald Crisp’s performance as Battling Burrows, Lucy’s violent father, is chilling in its portrayal of cruelty and brutality. Crisp, a versatile actor and director in his own right, brings an intensity to the role that makes Battling Burrows a memorable antagonist. His larger-than-life, menacing presence enhances the film’s sense of danger and serves as a constant reminder of the violence Lucy faces daily. Crisp’s performance is a stark contrast to the delicate connection shared by Lucy and Cheng, highlighting the film’s themes of innocence crushed by brutality.

The impact of Broken Blossoms extends beyond the performances. The film was groundbreaking in its emotional depth, pioneering the use of close-ups and soft-focus cinematography to create a heightened sense of intimacy that was rarely seen in early cinema. Its influence can be traced to later films that explore complex social issues and character-driven storytelling. Broken Blossoms also pushed the boundaries of what was acceptable to show on screen at the time, bringing social issues like domestic abuse and cultural prejudice to mainstream audiences, albeit through the lens of early 20th-century sensibilities.

While Griffith’s legacy remains complicated due to the racial stereotypes in some of his work, Broken Blossoms is often viewed as one of his most human and emotionally resonant films. The performances and visual techniques set a high standard for silent films that followed, helping establish cinema as a medium capable of conveying profound, layered stories.