The Dawn of Photography: Daguerreotype and Early Processes

By Boneapart / December 9, 2025 / No Comments / The Evolution of Photography

A Brief, Wandering Look at How Photography Actually Began

Long before we started stuffing our pockets with little rectangles that take 9,000 pictures of our pets, capturing an image—one image—was a miracle. You didn’t just point, click, and instantly regret your haircut. In the early 19th century, catching a moment on a surface was closer to alchemy: smoke, mirrors, fragile chemicals, and a frankly unreasonable amount of patience.

Before photography, the job of “show me what that looked like” belonged to painters and sketch artists. And while many of them were brilliant, the whole enterprise had one rather glaring limitation: most of us can’t afford someone to follow us around painting our faces. Visual memory was a luxury item.

Then along came a few stubborn geniuses who refused to leave well enough alone.

Daguerre, Niépce, and the First Time Light Stayed Put

Louis Daguerre didn’t invent photography alone. Before him was Nicéphore Niépce, a man who looked at sunlight and thought, Surely I can make this do something useful. In 1826, Niépce succeeded in producing the world’s first photograph—a ghostly roofline captured after days of exposure. Days. If he’d tried to photograph a person, the resulting picture would’ve been an empty chair and some existential questions.

When Niépce died, Daguerre kept pushing their work forward, eventually stumbling onto an honest breakthrough: the daguerreotype.

In 1839, he unveiled a process that made jaws drop and imaginations sprint. A silver-plated copper sheet was sensitized with iodine, exposed in the camera, then developed with mercury vapor—an excellent example of why early photographers tended not to live exceptionally long lives. But the results were stunning: razor-sharp images with a dreamy, mirror-like sheen. For the first time in history, a likeness didn’t rely on an artist’s interpretation. It simply was.

The world had never seen anything like it.

The Price of Innovation (and the Patience Required)

Of course, early daguerreotypes came with some caveats. Exposure times were long—minutes, not seconds—so portrait clients had to hold absolutely still. People were braced in place with metal stands, and even then, some portraits look suspiciously like someone trying not to sneeze.

The process was also delicate, expensive, and not exactly something you did casually in your kitchen unless you liked breathing mercury. Daguerreotypes were precious, easily damaged, and definitely not democratic—yet.

But that would change.

When Portraits Became Something Ordinary People Could Have

The arrival of the daguerreotype cracked open a door that painting couldn’t: suddenly the middle class could afford to preserve their own faces, their children, their families, their stories. Studios cropped up in cities across Europe and America, often with signage promising “Portraits in Only Ten Minutes!” which was considered outrageously fast.

People flocked to them. Families who had never owned a portrait of any kind now had the chance to hold their likeness in their hands. Victorian culture, which was deeply invested in memory and legacy, embraced this new form with almost religious devotion.

And yes, there was also the practice of post-mortem photography. It sounds macabre to us, but to families then, it was often the only image they ever had of a loved one. Photography allowed grief to hold on a little longer, and sometimes that was a comfort.

Photography as Witness to a Changing World

Daguerreotypes weren’t just used for faces. Photographers lugged their cumbersome equipment into cities, across landscapes, into newly industrializing streets, and onto scientific expeditions. Architecture, geography, natural science, politics—everything stood still long enough to be captured.

For the first time, the world could see itself with unfiltered clarity.

These early images became the visual memory of the 19th century. They recorded moments no painter could capture with such precision and neutrality. They helped explorers document lands, helped scientists record phenomena, and helped the public understand places they would never visit.

They made history visible.

Why These Little Silver Plates Still Matter

The daguerreotype didn’t last long as the dominant photographic process. Technology moved quickly—paper negatives, wet plates, dry plates, roll film, all the way to the glowing screens we now treat with both reverence and complete disregard.

But that first generation of images? They hold something no later technology ever fully replaced: a strange intimacy. Every daguerreotype is a tiny mirror holding a moment that someone once held still for. You can stand in front of one today and feel a human presence staring back at you from nearly two centuries away.

It’s the closest thing we have to time travel that doesn’t involve a suspicious doghouse or a malfunctioning wormhole.

Photography began with patience, chemicals, curiosity, and the stubborn belief that memories deserved to be made visible. And from those first shimmering plates, the entire world learned to see itself differently.

Famous Daguerreotypes:

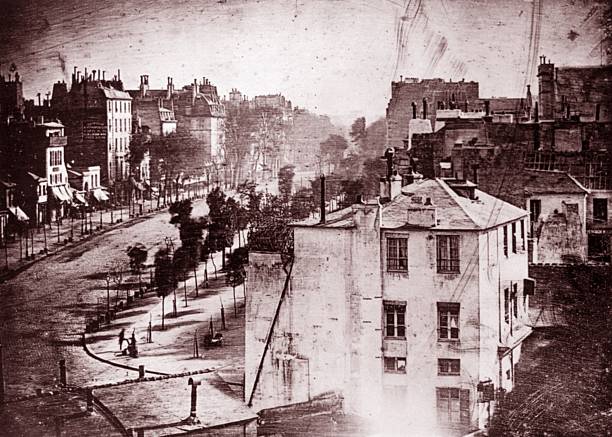

- The First Photograph of a Human

- Date: 1838

- Photographer: Louis Daguerre

- Description: This daguerreotype of the Boulevard du Temple in Paris is famous for being the first photograph to capture a human figure, a man having his shoes polished. Due to the long exposure time, moving subjects didn’t appear, but the stationary figures did.

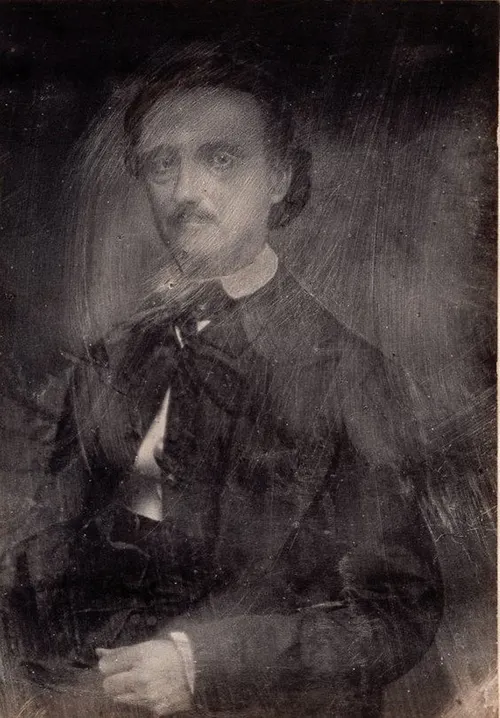

- Portrait of Edgar Allan Poe

- Date: 1849

- Photographer: William Abbott Pratt

- Description: A striking daguerreotype of the famous American writer Edgar Allan Poe, taken a few months before his death. This portrait is one of the most iconic images of Poe.

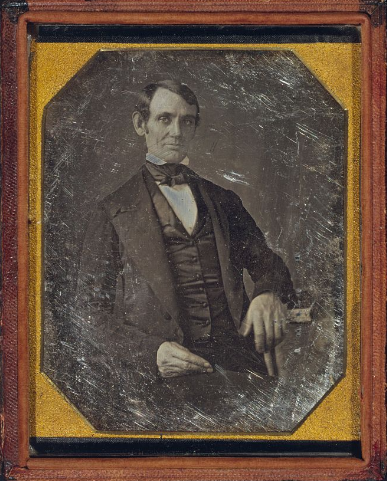

- Abraham Lincoln’s Early Portrait

- Date: 1846-1847

- Photographer: Nicholas H. Shepherd

- Description: One of the earliest known photographs of Abraham Lincoln, taken when he was still a lawyer in Springfield, Illinois, long before he became the 16th President of the United States.