Table of Contents

- The Dream of Color Photography

- The Context: Photography at the Turn of the Century

- The Autochrome Revolution

- Other Early Color Processes

- Screen Plate Methods: Paget and Dufaycolor

- Additive and Subtractive Color Processes

- Limitations and Challenges

- The Challenges of Color Photography

- Photographers of the Era

- Alfred Stieglitz: Champion of Modern Photography

- Lewis Hine: Photography as a Tool for Social Reform

- Gertrude Käsebier: Redefining Portraiture and Women’s Roles in Photography

- Also in The Evolution of Photography

The Dream of Color Photography

For much of the 19th and early 20th centuries, photography existed in shades of black, white, and gray. Despite its remarkable ability to capture the world with unprecedented accuracy, the medium always seemed incomplete—unable to reflect the vibrant hues of real life. The dream of color photography was a tantalizing goal, one that had captivated photographers, scientists, and inventors since the very dawn of the art form. How could one truly capture the golden glow of a sunset, the vivid greens of a summer meadow, or the myriad shades of human expression?

The early 20th century marked the beginning of a revolution in photography. As the industrial age surged forward, bringing new technologies and creative possibilities, so too did the quest to bring color to photography. Among these innovations, the Autochrome process—developed by the Lumière brothers in 1907—stood as a breakthrough. For the first time, photographers could capture the world in true color without resorting to laborious hand-coloring or chemical experiments. This was the first widely adopted color process, and it marked the birth of a new era in visual storytelling.

But the road to color was far from smooth. Autochrome and its contemporaries faced skepticism from a society accustomed to monochrome’s stark beauty. Challenges ranged from technical limitations to cultural perceptions of what photography should be. Despite these hurdles, early color photography began to reshape the medium, creating a foundation for the vivid, full-spectrum images we take for granted today.

The Context: Photography at the Turn of the Century

At the dawn of the 20th century, photography was a well-established medium, celebrated for its ability to capture life with clarity and precision. Yet, it was a world defined by grayscale. Black-and-white photography dominated not only for its technical simplicity but also because it had become synonymous with the art form itself. The crisp contrast of monochrome images, whether in portraits, landscapes, or photojournalism, was widely regarded as the pinnacle of photographic achievement.

The preference for black-and-white wasn’t merely a matter of practicality; it was deeply rooted in cultural perceptions. Many artists and critics of the time viewed photography as an inherently artistic medium, one that could transcend the chaotic vibrancy of life by reducing it to its essential tones. Monochrome images, they argued, provided a timeless and universal aesthetic, free from the distractions of color. As a result, even as inventors experimented with color photography, the broader public and artistic community often resisted these efforts.

Behind this cultural hesitation lay formidable technical challenges. Early attempts at color photography were both complicated and inconsistent. Processes like daguerreotypes and albumen prints, while revolutionary for their time, were ill-suited to capturing color. For much of the 19th century, color in photography meant hand-coloring prints with painstaking detail—an artistic endeavor in its own right but far from the direct capture of reality that color photography promised.

The desire to capture the world in color, however, remained strong. By the late 19th century, advancements in chemistry and optics were beginning to make true color photography seem possible. The question wasn’t if color photography could be achieved but how it could be done in a way that was practical, affordable, and, perhaps most importantly, beautiful.

This was the context in which the Lumière brothers, and other innovators, began their work. The Autochrome process that they introduced in 1907 didn’t just solve a technical puzzle—it challenged the very notion of what photography could and should be. It was an invention born out of a world eager for progress yet reluctant to abandon tradition, paving the way for one of the most transformative eras in photographic history.

The Autochrome Revolution

In 1907, the world of photography experienced a seismic shift with the introduction of the Autochrome process, a groundbreaking invention by the French Lumière brothers, Auguste and Louis. Known for their contributions to cinema, the Lumières turned their attention to solving one of photography’s most enduring challenges: capturing true color. With Autochrome, they not only succeeded but also ignited a revolution in how the medium was perceived and practiced.

The Autochrome process was unlike anything that had come before. At its heart was a simple yet ingenious idea: using dyed starch grains to create a color filter. Microscopic grains of potato starch were dyed in shades of orange, green, and violet, then evenly spread across a glass plate and coated with a photosensitive emulsion. When exposed to light, this layer acted as both a filter and a recording medium, capturing the colors of the scene with remarkable accuracy. The result was a single glass plate image that shimmered with soft, painterly hues.

For photographers, Autochrome offered something unprecedented: the ability to capture color directly, without the labor-intensive hand-coloring methods of the past. It was a technical triumph that brought the dream of color photography closer to reality. While the process required long exposure times and careful handling, it was far more practical than earlier attempts at color, making it accessible to a growing number of enthusiasts and professionals.

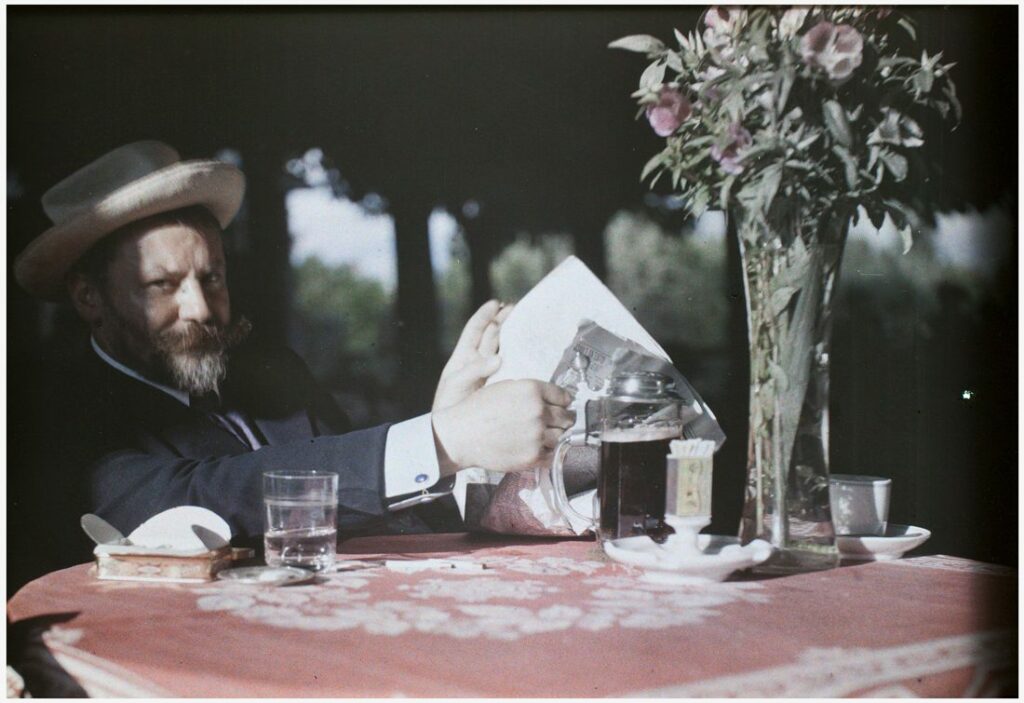

The impact of Autochrome wasn’t merely technical; it was profoundly artistic. The images produced by this process possessed a luminous, ethereal quality that captivated viewers. Portraits appeared more lifelike, landscapes more vivid, and everyday scenes were imbued with a sense of immediacy and intimacy. Early adopters of Autochrome included prominent photographers and artists who recognized its potential as a new mode of expression. The process quickly gained popularity among creative circles, solidifying its place in the history of photography.

Public reaction to Autochrome was mixed. On one hand, the vibrant images inspired wonder and curiosity, offering a glimpse of what the future of photography might hold. On the other hand, the process was expensive, and its results, while beautiful, were seen by some as less precise or dramatic than black-and-white images. Critics argued that the dreamlike quality of Autochrome lacked the stark realism and gravitas associated with monochrome photography.

Despite these reservations, the Autochrome process marked a turning point. It demonstrated that color photography was not just a theoretical possibility but a practical reality. Though limited by cost and technical constraints, Autochrome’s popularity laid the groundwork for further innovations in color photography, inspiring a wave of experimentation that would continue throughout the early 20th century.

In its shimmering colors and soft focus, Autochrome captured more than just the visual world—it captured an era of discovery and transition. It was the first step toward a new way of seeing, one that would forever change the art and science of photography.

Other Early Color Processes

While Autochrome became the most celebrated early color photography process, it was not the only method being explored in the early 20th century. Other inventors and companies sought to develop alternatives that could overcome some of Autochrome’s limitations, particularly its expense and the challenges of working with glass plates. These competing processes, though less well-known today, represent important milestones in the journey toward capturing life in color.

Screen Plate Methods: Paget and Dufaycolor

Building on the principles of Autochrome, other screen plate methods emerged, offering different approaches to achieving color imagery. The Paget process, introduced around 1913, employed a similar concept, using a screen plate to filter colors. However, instead of dyed starch grains, it utilized a regular grid pattern of color filters, which provided slightly sharper images. While the Paget process promised improvements in image clarity, it never achieved the same popularity as Autochrome due to its complexity and cost.

Dufaycolor, developed in the 1920s, represented a significant step forward. This process used a series of tiny, overlapping colored lines printed directly onto a transparent film base. Unlike Autochrome and Paget, Dufaycolor eliminated the need for a glass plate, making it lighter and more versatile. It became a preferred method for amateur photographers who valued its portability, though it still faced stiff competition from black-and-white photography, which remained dominant due to its lower cost and greater convenience.

Additive and Subtractive Color Processes

As screen plate methods evolved, new approaches to color photography began to emerge. These fell into two categories: additive and subtractive processes. Additive processes, like Autochrome and its contemporaries, relied on mixing colors directly on the image surface through overlapping patterns of red, green, and blue. While effective, these methods often suffered from limited sharpness and inconsistent color balance.

The subtractive color method, which would later dominate the field, worked differently. By layering cyan, magenta, and yellow dyes, subtractive processes allowed for more precise color reproduction and better image clarity. These techniques were still in their infancy during the Autochrome era but would come into their own with the introduction of Kodachrome in 1935, which revolutionized color photography with its rich tones and fine grain.

Limitations and Challenges

Despite their promise, these early processes shared many of the same limitations as Autochrome. The materials were expensive, making color photography a luxury rather than a widespread practice. Exposure times were often lengthy, requiring subjects to remain perfectly still for minutes at a time. Furthermore, the resulting images, though beautiful, lacked the sharpness and detail of black-and-white photographs.

For these reasons, color photography remained a niche art form, embraced by enthusiasts and innovators but not yet practical for the masses. However, the competing processes of this period demonstrated the relentless drive to perfect color photography. Each new invention brought incremental improvements, paving the way for the breakthroughs of the 1930s and beyond.

While Autochrome may have been the first major success, it was far from the end of the story. The Paget process, Dufaycolor, and the emergence of subtractive techniques show how the photographic community continued to push the boundaries of what was possible. These early efforts, though imperfect, laid the foundation for the vibrant, full-color imagery we take for granted today.

The Challenges of Color Photography

The advent of color photography was a monumental leap forward, but it did not come without its share of obstacles. Both technically and culturally, the transition from black-and-white to color was fraught with challenges that limited its initial acceptance and widespread adoption. For many, color photography in its early stages was an ambitious experiment rather than a practical tool for everyday use.

Technical Challenges

One of the most significant barriers to early color photography was its complexity. Processes like Autochrome, Paget, and Dufaycolor required specialized equipment and materials, which were both expensive and difficult to handle. Autochrome, for example, relied on glass plates coated with dyed starch grains, making them fragile and cumbersome. Additionally, these processes demanded long exposure times, particularly in low-light conditions, forcing photographers to work with stationary subjects and ideal lighting setups.

The results, while groundbreaking, were often inconsistent. Early color processes struggled with color accuracy, leading to images that might appear too muted, overly vibrant, or prone to color shifts. The grainy texture of methods like Autochrome, caused by the uneven distribution of starch grains, was another limitation that detracted from the sharpness and clarity of the images. Compared to the crisp detail achievable with black-and-white photography, early color photographs often seemed less refined.

Printing and reproducing color photographs added another layer of difficulty. Unlike black-and-white prints, which could be easily developed and duplicated, color photographs required intricate procedures that varied depending on the process. This made it challenging to produce multiple copies of a single image, limiting the medium’s practicality for commercial and journalistic purposes.

Cultural Resistance

Beyond the technical hurdles, early color photography faced significant cultural resistance. Black-and-white photography, which had dominated the medium for decades, was deeply entrenched in the public consciousness. It was seen as the standard for both artistic and documentary purposes, celebrated for its dramatic contrasts and timeless elegance. Critics often argued that the addition of color detracted from photography’s artistry, reducing it to mere replication of reality.

In the world of journalism, color photography was viewed with suspicion. The vivid hues of color images were sometimes perceived as less serious or even garish compared to the stark, authoritative look of monochrome. For decades, black-and-white remained the preferred choice for newspapers and magazines, particularly for reporting on serious subjects.

Cost also played a role in slowing the acceptance of color photography. Materials like Autochrome plates and the chemicals required for developing were prohibitively expensive for most amateur photographers, keeping the technology out of reach for the average household. This reinforced the perception that color photography was a luxury, reserved for high-end artistic pursuits rather than practical or everyday use.

The Tension Between Realism and Art

Another fascinating challenge was the philosophical debate over the role of color in photography. While some celebrated the potential of color photography to more accurately capture the world as it appeared to the human eye, others felt that this realism came at the expense of artistic expression. The soft, dreamlike quality of Autochrome images, for example, was embraced by some photographers but criticized by others as lacking the sharp focus and dramatic contrasts of black-and-white photography.

This tension underscored a broader question: was photography meant to document reality, or was it an art form in its own right? Color photography blurred these boundaries, prompting heated debates about the medium’s purpose and potential.

A Step Toward the Future

Despite these challenges, the seeds of change had been planted. The technical limitations of early processes spurred innovation, while cultural resistance gradually gave way to curiosity and admiration for the new possibilities of color. The advent of Autochrome and its contemporaries demonstrated that color photography was not just a novelty but a medium with transformative potential.

The road to widespread adoption was still long, but the early pioneers of color photography laid a foundation that would eventually lead to the vibrant, ubiquitous images that define modern photography today.

Photographers of the Era

Alfred Stieglitz: Champion of Modern Photography

Alfred Stieglitz was a towering figure in early 20th-century photography, redefining the medium’s artistic possibilities. He was a key proponent of the Pictorialist movement, which treated photography as a form of fine art akin to painting, emphasizing mood and atmosphere over sharp realism. Stieglitz’s later work, however, championed “straight photography,” a style that celebrated clarity, precision, and honesty. His iconic 1907 photograph The Steerage, which captures the stark divide between social classes on a transatlantic ship, exemplifies his ability to blend documentary realism with artistic expression. Beyond his photography, Stieglitz’s contributions as a gallery owner and publisher were vital to elevating the status of photography as a serious art form. Through his gallery “291” and his journal Camera Work, Stieglitz introduced the world to groundbreaking photographers and modernist artists alike.

Lewis Hine: Photography as a Tool for Social Reform

Lewis Hine demonstrated the power of photography as a force for social change. Working with the National Child Labor Committee in the early 20th century, Hine traveled across the United States, documenting the harsh realities of child labor in factories, mines, and farms. His poignant images, such as the haunting portrait of a young cotton mill worker, brought the exploitation of children to public attention and helped galvanize support for labor reforms. Hine’s work combined stark realism with deep empathy, capturing his subjects’ humanity while shedding light on systemic injustices. By the 1920s, Hine also documented the construction of iconic landmarks like the Empire State Building, creating images that celebrated the dignity of labor. His work remains a powerful reminder of photography’s ability to advocate for social justice.

Gertrude Käsebier: Redefining Portraiture and Women’s Roles in Photography

Gertrude Käsebier was one of the most influential women in early photography, known for her evocative portraits and her dedication to elevating photography as an art form. Her work often explored themes of motherhood, femininity, and domestic life, offering an intimate and emotional perspective that set her apart from her contemporaries. Käsebier’s portraits of Native Americans, particularly those of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West performers, combined cultural sensitivity with artistic elegance. A founding member of the Photo-Secession movement alongside Alfred Stieglitz, she played a crucial role in legitimizing photography as a fine art. Käsebier’s success as a professional photographer also broke barriers for women in a field that was predominantly male, inspiring future generations of female photographers.