Table of Contents

The Aesthetic Movement (1890s–1910s)

Introduction

In the late 19th century, photography found itself at a crossroads. Long regarded as a tool for documentation and portraiture, it began to enter a new phase, one where photographers sought to align their craft more closely with the expressive nature of traditional art forms. This period, spanning the 1890s to the 1910s, marked the rise of Pictorialism—a movement that reshaped photography by emphasizing mood, beauty, and artistic intention over strict realism.

Photographers within this movement wanted to prove that their medium could do more than capture the world as it appeared; they believed it could reveal deeper, often unseen, layers of emotion and atmosphere. Drawing from the ideals of the Arts and Crafts movement, which valued hand-crafted beauty and individual expression, Pictorialists saw their darkrooms as studios and their photographs as canvases. They employed experimental techniques to produce images that echoed the soft, painterly qualities of impressionist and romantic art, seeking to evoke rather than merely record.

This blog will explore the roots of Pictorialism, its defining techniques, and the key figures who championed photography’s artistic potential. We’ll also look at how the movement helped shift public perception, opening the door for photography to stand alongside painting and sculpture as a respected art form. Through their dedication to craft and vision, Pictorialist photographers not only expanded the possibilities of the medium but laid the groundwork for the modern view of photography as an art deeply capable of expression and innovation.

Origins of Pictorialism

Before photography was seen as an art form, it served a primarily documentary role. Invented in the early 19th century, photography was celebrated for its remarkable ability to record reality with detail unmatched by painters or sketch artists. Yet, while photographers captured accurate portraits, landscapes, and scenes of everyday life, their work was often viewed as a mechanical process—one that lacked the personal vision and emotional resonance associated with traditional fine arts. By the 1890s, however, this perception was beginning to shift, and photography found itself influenced by broader cultural trends that redefined what art could be.

One of these influential movements was the Arts and Crafts movement, which celebrated beauty in craftsmanship and sought to counter the impersonal effects of industrialization. Founded in England by artists and designers like William Morris, the Arts and Crafts movement valued art that was both personal and handcrafted, emphasizing aesthetic quality over utility. This philosophy inspired photographers who longed to imbue their work with similar values, bridging the gap between photography and the expressive ideals of painting.

Out of this backdrop arose Pictorialism, a photographic movement that treated photography as a means to express subjective beauty and evoke feeling. Pictorialist photographers rejected the straightforward realism that characterized early photography, instead focusing on creating images that conveyed emotion, atmosphere, and symbolic depth. Just as painters chose their colors, textures, and brushstrokes to create a mood, Pictorialists used unique techniques to infuse their images with an artistic touch.

By defining photography as a medium capable of expressing ideas and emotions, Pictorialists redefined the expectations of their craft. Photography could be more than a mirror to the world; it could be a window into the mind and spirit of the photographer. Through this approach, Pictorialism laid the groundwork for a new understanding of photography as an art form, one that drew as much from the artist’s vision as it did from the reality before the lens.

Techniques and Aesthetic Approaches in Pictorialism

To Pictorialists, photography was not merely about what the eye could see but what the heart could feel. In their quest to elevate photography into the realm of fine art, these photographers embraced a range of creative techniques to produce images that conveyed mood and meaning, often with a dreamlike or painterly quality. By manipulating both the camera and the darkroom process, Pictorialists created photographs that broke away from realism, aiming instead to capture something deeper and more personal.

One of the most distinctive aesthetic choices in Pictorialism was the use of soft focus. Unlike the sharp, clear images typical of early photography, Pictorialists preferred a softer, blurred look, which allowed them to suggest rather than depict. This gentle, ethereal effect not only reduced harsh details but also brought a sense of atmosphere to their work. By carefully controlling focus, they could mimic the subtle transitions of light and shadow seen in paintings, inviting viewers to interpret an image’s emotional undertone rather than simply taking in its visual details.

In addition to soft focus, Pictorialists employed various manipulative processes that gave them greater control over the final appearance of their images. Techniques like gum bichromate printing, platinum printing, and combination printing allowed photographers to alter elements of the photograph, adding textures, enhancing tones, or even combining multiple negatives to create a composite image. Gum bichromate, for instance, allowed artists to hand-apply pigments to their images, giving them the ability to adjust colors and textures directly. Platinum printing, known for its rich tonal range, gave images a matte, painterly quality that was far removed from the glossy, commercial look often associated with photography at the time.

Pictorialist photographers also approached composition and mood with the careful eye of a painter. They often arranged their subjects to evoke classical themes or emotional narratives, using light, shadow, and setting to heighten the symbolic or emotional weight of an image. Whether capturing a misty landscape, a solitary figure in contemplation, or a tender portrait, Pictorialists chose their scenes and subjects with intention, framing each photograph to express a particular mood or story. This emphasis on composition helped reinforce the notion that photographs could be designed and expressive, not merely captured.

Finally, the darkroom itself became a creative space where photographers could refine their vision. For Pictorialists, developing a photograph was not merely a technical step but an opportunity for experimentation and artistry. Here, they could adjust contrast, manipulate textures, and experiment with different chemical processes, treating the photograph as a canvas to be shaped and perfected. This commitment to altering and enhancing the image blurred the line between photography and other visual arts, underscoring Pictorialism’s view of photography as a medium that required both artistic skill and creative intention.

Through these techniques, Pictorialists transformed photography into something that could embody the artist’s inner world, reaching beyond the realm of documentation into the domain of expression. Their methods established a new standard for what photography could achieve, proving that even in a medium defined by light and chemistry, there was room for vision, emotion, and art.

Key Figures of the Pictorialist Movement

The Pictorialist movement was not only a stylistic revolution but also a gathering of visionary artists who pushed the boundaries of photography, believing it could achieve the same expressive depth as painting or sculpture. These photographers, driven by their dedication to aesthetic and emotional nuance, laid the foundation for photography’s acceptance in the art world. Among the most influential of these figures were Alfred Stieglitz, Edward Steichen, Gertrude Käsebier, and Clarence H. White, each of whom contributed uniquely to the movement’s development and legacy.

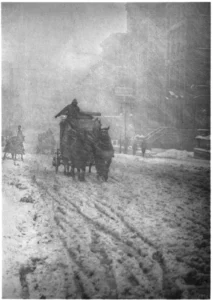

Alfred Stieglitz is perhaps the best-known champion of Pictorialism and one of the most influential figures in early art photography. His dual roles as a photographer and promoter of photography as fine art gave the movement much of its momentum. Through his iconic publication, Camera Work, and his New York gallery, 291, Stieglitz created spaces where photography was celebrated alongside paintings and sculptures. His own work exemplified the Pictorialist aesthetic, often capturing urban scenes and natural landscapes in a soft, atmospheric style. Stieglitz believed that photography could transcend its mechanical origins and convey the same emotional intensity as any other art form. His dedication to this vision helped shift public perception, establishing photography as a legitimate art form in both the United States and Europe.

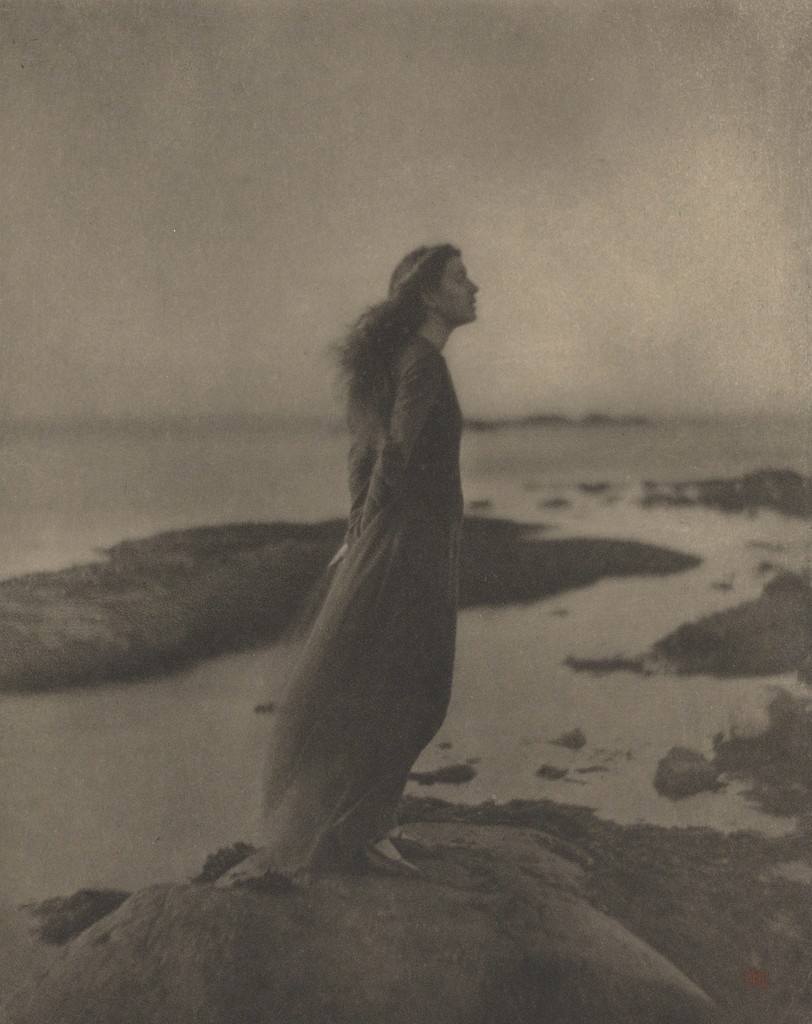

Edward Steichen, a frequent collaborator of Stieglitz, was another major figure in the Pictorialist movement. Steichen’s early work embodied the romantic, ethereal qualities associated with Pictorialism, as he used soft focus, dramatic lighting, and innovative darkroom techniques to create images that felt more like paintings than photographs. Steichen’s portraits, particularly those of prominent artists and writers, had an intimacy and atmospheric quality that was unprecedented. His experiments with color processes, such as the autochrome, added depth and richness to his images, further distinguishing photography as an expressive art form. Steichen’s influence on the movement extended internationally, as he exhibited widely and helped to establish photography as an art form in both America and Europe.

.jpg?mode=max&width=1025)

One of the movement’s pioneering women, Gertrude Käsebier brought her own perspective and sensitivity to Pictorialism, particularly through portraiture. Käsebier’s work often focused on themes of motherhood, family, and femininity, capturing her subjects with an emotional depth that was rare in portrait photography at the time. Her portraits featured a soft, warm style that humanized her subjects, inviting viewers to consider their inner lives rather than merely their outer appearances. Käsebier’s success and recognition as a woman in a male-dominated field was groundbreaking, and her work inspired future generations of female photographers. Through her leadership in the movement and her role in the founding of the Photo-Secession group with Stieglitz, Käsebier helped shape the way portraiture could convey personal and universal themes alike.

Finally, Clarence H. White contributed a gentle, introspective quality to the Pictorialist movement. Known for his softly lit domestic scenes and portraits, White’s work often depicted quiet, reflective moments, capturing everyday life with an artist’s eye. His compositions were carefully constructed, emphasizing harmony and tranquility, often with figures posed in natural, contemplative ways. White was also influential as a teacher, eventually founding the Clarence H. White School of Photography, where he trained a new generation of photographers in both technical skills and aesthetic sensibilities. His emphasis on education and craft helped solidify the artistic values that defined Pictorialism, inspiring others to see photography as a medium for personal expression.

Impact on the Perception of Photography in the Arts

The Pictorialist movement did more than define a new aesthetic for photography; it fundamentally transformed how the medium was perceived by the public and the art world alike. By focusing on atmosphere, mood, and craftsmanship, Pictorialists proved that photography could be more than just a tool for scientific or documentary purposes. Through exhibitions, publications, and tireless advocacy, they succeeded in positioning photography as a form of high art—a shift that would have profound implications for the field.

A Shift in Public Perception

One of the most significant achievements of Pictorialism was its influence on public perception. Before this movement, photography was seen primarily as a technical process, with limited room for artistic interpretation. It was celebrated for its precision and clarity but often dismissed as a lesser form, unable to achieve the emotional and intellectual impact of painting or sculpture. The Pictorialists challenged this notion by presenting photographs that emphasized beauty, symbolism, and expression. By introducing the idea that photographs could evoke the same emotional response as a painting, Pictorialists reshaped how audiences and critics understood photography’s potential.

Art Galleries and Photographic Exhibitions

Exhibitions played a crucial role in this transformation. Alfred Stieglitz’s 291 Gallery in New York became one of the first places where photographs were displayed alongside works by painters and sculptors, elevating the status of photography in the eyes of art connoisseurs and the general public alike. Stieglitz’s gallery and other exhibitions provided a platform for photographers to showcase their work as art, helping audiences to view photography as a medium worthy of artistic consideration. These shows exposed people to images that went beyond simple representation, encouraging viewers to appreciate photography’s capacity for depth, mood, and narrative.

Similarly, publications like Camera Work—a quarterly journal founded by Stieglitz—were instrumental in advancing the dialogue about photography’s artistic potential. Camera Work featured high-quality reproductions of Pictorialist photographs and included essays and critical commentary that argued for photography’s place in the fine arts. By promoting photography in such an intellectually rigorous context, Pictorialists fostered a new level of respect for the medium. The journal’s influence reached photographers and art lovers across the United States and Europe, helping to cultivate a community that recognized and celebrated photography’s artistic possibilities.

Influence on Later Movements

While Pictorialism eventually faded as new styles emerged in the 1920s, its influence can be traced in the development of Modernism in photography and other later movements. By proving that photography could be an interpretive, expressive medium, Pictorialism laid the foundation for a more experimental approach to photography. The movement’s emphasis on mood, composition, and personal vision created a lasting appreciation for photography as a creative discipline, paving the way for modernist photographers who would continue to push the boundaries of the form.

Later movements, such as Surrealism and Abstract photography, were able to take inspiration from the groundwork laid by Pictorialists, embracing the idea that photographs could capture not only what was visible but also what was imagined or felt. Without the Pictorialist movement’s early advocacy for photography as an art form, these later movements may not have found the fertile ground necessary to thrive. The concept that photographs could embody symbolism, fantasy, and abstraction—principles Pictorialists introduced—would become central to the evolution of art photography in the 20th century.

Legacy of the Pictorialist Movement

The impact of Pictorialism did not end when the movement’s popularity began to wane in the 1920s. Instead, its emphasis on artistic intention, mood, and emotional resonance left a lasting legacy that continues to influence both photographic art and education. By challenging the boundaries of what photography could express, Pictorialists laid the groundwork for the medium’s evolution, inspiring generations of photographers and artists to view the camera not merely as a tool for recording but as an instrument for creating.

Artistic Values in Contemporary Photography

Today, many of the values championed by Pictorialists—such as mood, composition, and the artist’s vision—remain central to fine art photography. While photography has since embraced countless styles, from documentary realism to abstract experimentation, the idea that a photograph can be more than a straightforward capture of reality persists. Many contemporary photographers continue to explore ways to convey emotion, symbolism, and narrative through their work, echoing the Pictorialist ideal that the camera can be used to interpret rather than simply record. Fine art photography, now a widely respected genre, owes much of its ethos to the Pictorialist movement’s early dedication to beauty and personal expression.

Educational Influence and the Role of Craft

The movement’s influence extends beyond aesthetics, reaching into the heart of photography education. Pictorialist pioneers like Clarence H. White helped set a precedent for formal photographic education that emphasizes both technical skill and creative vision. White’s photography school, one of the first of its kind, focused on teaching students not only how to use their cameras but also how to approach photography as a form of artistic expression. This commitment to balancing technique with artistry remains a cornerstone of photography education today, with many schools and programs continuing to teach historic Pictorialist methods—such as soft focus, darkroom manipulation, and alternative printing techniques—as part of their curricula. In this way, the Pictorialist legacy lives on in the training of new generations who approach photography as an art form.

Revival of Vintage Techniques

In recent years, there has been a renewed interest in vintage photographic processes, many of which were championed by the Pictorialists. Techniques like platinum printing, gum bichromate, and hand-tinted photography are experiencing a revival among photographers who are drawn to the tactile, hands-on aspects of early photographic methods. For these artists, using historical processes is a way to connect with the medium’s roots and bring a sense of craftsmanship to their work, echoing the Pictorialist belief that the darkroom could be a place of creativity and artistry. This resurgence speaks to the enduring appeal of the Pictorialist movement’s methods and the timeless quality of its aesthetic values.

A Foundation for Expression in Photography

Perhaps the most significant legacy of Pictorialism is its contribution to the idea that photography, like any art form, can reveal the inner world of the artist. By valuing subjective vision and personal interpretation, Pictorialists introduced a new way of thinking about photography—one that emphasized individual perspective and emotion. This philosophy has had a profound influence on the evolution of photographic genres, inspiring photographers to pursue styles as varied as surrealism, conceptual photography, and even digital art. Pictorialism’s emphasis on beauty, feeling, and personal voice remains relevant in today’s diverse photographic landscape, where artists continue to explore ways to convey meaning through their images.

In reimagining photography as an expressive and artistic medium, the Pictorialists set the stage for a world in which photography is celebrated not only for what it shows but for what it suggests and reveals. Their vision of photography as an art has transcended time, inspiring photographers to view their work as a blend of technical skill and artistic insight. The movement’s influence continues to be felt today, as photographers and educators draw inspiration from the pioneers who believed that every photograph could be a work of art.