Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Early Life and Career of Len Spencer

- The Rise of Len Spencer’s Cylinder Recordings

- Impact of Wax Cylinder Recordings

- Decline of the Cylinder Era and Spencer’s Later Career

Introduction

Len Spencer was one of the earliest stars of the American recording industry, and his voice became a familiar sound in homes across the country during the late 1800s and early 1900s. With a career that blended comedy, music, and vaudeville, Spencer had a talent for making people laugh and entertaining them with his energetic performances. But what really set him apart was how he embraced the new technology of his time: wax cylinders. Long before records became the norm, these cylinders were how people first experienced recorded sound, and Spencer was right there at the forefront.

Wax cylinders, made from delicate, grooved wax, were the first widely used format to capture and play back audio. For the first time, people could bring performances into their living rooms without needing to attend a live show. It was a game-changer, and Spencer became one of the most popular performers to take advantage of this new medium. His recordings of comic monologues, lively sketches, and humorous dialogues became hits, giving listeners a taste of the vaudeville stage without leaving home.

In this post, we’ll take a closer look at Len Spencer’s incredible career, the impact of his wax cylinder recordings, and why his work still resonates with those who are passionate about the history of sound.

Early Life and Career of Len Spencer

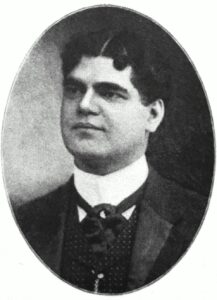

Len Spencer was born on February 12, 1867, in Washington, D.C., into a family that seemed destined for the public eye. His father, Platt Spencer, was a political figure and businessman, and young Len grew up surrounded by an entrepreneurial spirit. While his family’s background may have pointed him toward a traditional path in politics or business, Len was drawn to something entirely different: the stage.

As a young man, Spencer found his footing in vaudeville, where his natural charisma and knack for performance made him a standout. Vaudeville, with its eclectic mix of comedy, music, and theatrical acts, was the perfect training ground for Spencer’s talents. Whether he was delivering a comic monologue or playing a character in a lively sketch, he knew how to hold an audience’s attention and keep them laughing.

It wasn’t long before Spencer’s talents caught the attention of the recording industry, which was in its infancy in the 1890s. At the time, companies like Edison and Columbia Phonograph were just beginning to explore the possibilities of capturing sound on wax cylinders, and they needed performers with big personalities and even bigger voices to make an impression on the new medium. Spencer fit the bill perfectly.

He transitioned seamlessly from live performances to recorded ones, becoming one of the first artists to embrace the new technology. His ability to adapt his stage routines to the limitations of early recording—where exaggerated enunciation and clear delivery were essential—set him apart from others. By the mid-1890s, Len Spencer had become one of the most popular recording artists of his time, bringing his vaudeville charm into homes across America, one wax cylinder at a time.

The Rise of Len Spencer’s Cylinder Recordings

As wax cylinders gained popularity, Len Spencer’s career truly took off, with his recordings becoming staples in American homes. His real strength lay in comic monologues, humorous skits, and vaudeville-style routines, which were perfectly suited for the short length and clarity needed in early sound recordings. Spencer had a voice that carried well through the limitations of the cylinder format, and his expressive style made even the simplest comedic sketches come alive for listeners.

One of his most notable recordings was “Arkansaw Traveler,” a comedic dialogue between a country traveler and a fiddler, full of wit and playful banter. This piece showcased Spencer’s ability to play multiple characters and use his voice to create a vivid scene, something that was incredibly engaging for listeners at the time. The routine’s mix of humor and storytelling was a prime example of what made vaudeville so popular, and it translated beautifully into this new medium.

Another standout was his rendition of “Casey at the Bat,” the famous baseball poem by Ernest Thayer. Spencer’s booming voice and theatrical delivery brought the poem to life, turning it into a dramatic monologue that captured the excitement and heartbreak of a fictional baseball game. This recording became one of the most popular recitations of the era, and Spencer’s version was a definitive take on a beloved American story.

Then there’s “Cohen at the Telephone,” a humorous monologue that poked fun at the growing role of telephones in everyday life. Spencer’s portrayal of a Jewish immigrant attempting to navigate this new technology was a comedic hit, reflecting the everyday frustrations and cultural shifts that many Americans were experiencing at the time. The piece highlighted Spencer’s talent for ethnic humor, which was common in vaudeville, though often problematic by modern standards.

Spencer wasn’t just a solo act, though. He frequently collaborated with other performers, including popular vaudeville and minstrel artists like Billy Golden. Together, they recorded duo performances that brought even more energy and variety to the wax cylinder market. Their chemistry on recordings helped popularize the use of back-and-forth dialogue and dynamic interaction in recorded sound. This collaborative spirit was essential to the vaudeville tradition, and Spencer carried it over seamlessly into the world of recorded music and comedy.

These recordings weren’t just entertainment; they were a reflection of American tastes at the turn of the century. Humor rooted in everyday life, playful character sketches, and dramatic recitations all resonated with a public hungry for this new way to experience entertainment. Spencer’s ability to adapt vaudeville and spoken-word performances to the limits of wax cylinders made him a household name and a key figure in early recorded sound.

Impact of Wax Cylinder Recordings

Cylinder Technology

Wax cylinders were one of the first commercially viable ways to record and play back sound, and their introduction in the late 19th century revolutionized entertainment. Invented by Thomas Edison in 1877, these cylindrical records were made of wax and featured tiny grooves that could capture sound when rotated against a stylus. For the first time, music, spoken word, and live performances could be recorded, stored, and replayed. This breakthrough allowed audiences to experience entertainment without needing to be physically present at a show—a revolutionary idea at the time.

However, the technology had its challenges. Wax cylinders were fragile, easily damaged, and had limited recording time—usually around two to three minutes per cylinder. Recording on them required precision, and performers had to adjust their styles to ensure their voices carried clearly and loudly enough to be captured by the equipment. Despite these limitations, the format was incredibly popular from the 1890s into the early 1900s, especially for comedic performances and vaudeville sketches. The short duration of the cylinders was perfect for quick, punchy comedy routines, which is why Len Spencer’s humorous monologues and skits fit so well into this format.

Spencer’s recordings capitalized on the advantages of cylinder technology, delivering tightly crafted performances that worked within the time and technical constraints. He knew how to use his voice to project personality, humor, and story, despite the lack of visual elements or extensive sound effects. In many ways, the limitations of the cylinder helped shape the style of early recorded entertainment.

Cultural Impact

Wax cylinder recordings had a profound effect on American popular culture, and Len Spencer was one of the pioneers shaping this new landscape. At a time when entertainment options were limited to live performances, printed books, or sheet music, cylinders brought sound into homes for the first time. People who had never been able to see a vaudeville show could suddenly hear it in their living rooms, broadening the reach of artists like Spencer and making entertainment more accessible to the masses.

Spencer’s recordings, in particular, played a key role in shaping the early world of recorded entertainment. His comic monologues, recitations, and sketches were designed for mass appeal, and they resonated with a wide and diverse audience. His ability to tell engaging, funny stories in just a few minutes made him a favorite among listeners who were new to this type of entertainment. He tapped into the humor of everyday life, often portraying characters that reflected the experiences of his listeners—whether it was a frustrated telephone user in “Cohen at the Telephone” or a bumbling country traveler in “Arkansaw Traveler.”

These recordings also reflected broader social trends of the time. Vaudeville, with its variety of short, punchy acts, was immensely popular during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and Spencer’s work drew directly from that tradition. The vaudeville style allowed for playful satire, ethnic humor, and slapstick routines that mirrored the melting pot of American society at the time, though it also came with its share of problematic stereotypes. Spencer’s work, like much of early vaudeville, captured both the charm and the complexities of turn-of-the-century entertainment.

Beyond his comedy, Spencer helped shape the cultural perception of recorded entertainment itself. He was a bridge between the live stage and the recording studio, showing how performances could be adapted for an entirely new medium. As a result, he helped usher in the modern era of recorded sound, paving the way for future artists to explore the potential of audio as a standalone art form. Spencer’s success on wax cylinders not only solidified his own fame but also highlighted the growing cultural demand for recorded sound, which would eventually lead to the dominance of the record industry.

In a time when vaudeville shows were regional and often inaccessible to rural audiences, Spencer’s recordings brought the essence of these performances to a national audience. He helped define what recorded comedy could be, and his work on wax cylinders laid the groundwork for future generations of performers and the eventual explosion of recorded music and spoken word entertainment.

Decline of the Cylinder Era and Spencer’s Later Career

Decline of Cylinder Technology

As revolutionary as wax cylinders were in their heyday, technological advancements quickly outpaced them. By the early 20th century, cylinder recordings were being overshadowed by disc records, like the 78 RPM format, which offered better sound quality and longer playing time. The flat disc format, popularized by companies like Victor Talking Machine Company and Columbia Records, was easier to mass-produce and store, making it more appealing to consumers. For Len Spencer and other artists who had built their careers on cylinder recordings, this shift posed a challenge.

The obsolescence of cylinder technology began in the 1910s, and by the end of the decade, discs had largely taken over as the dominant medium for recorded sound. As the industry moved toward discs, many early recording artists, including Spencer, had to adapt to the new format or risk being left behind. While Spencer was able to continue recording during this period, the industry’s focus on newer technologies and trends meant that the wax cylinder, once the cutting edge of audio recording, was quickly fading into history.

Spencer’s Adaptation

Spencer, ever the versatile performer, did not fade into obscurity immediately. He continued to work in the recording industry, cutting discs for companies like Columbia and Victor as the cylinder market declined. However, the transition wasn’t seamless. While he had been a leading figure during the cylinder era, his prominence in the industry began to wane as new stars and genres emerged. The rise of ragtime music, jazz, and other musical trends of the early 20th century meant that spoken-word comedy and vaudeville routines—Spencer’s bread and butter—were becoming less central to popular recorded entertainment.

As the focus of the recording industry shifted, Spencer found himself recording less frequently, though he remained active in vaudeville and the entertainment world. He had already made his mark, but the peak of his career had passed with the decline of the cylinder. While he remained a respected figure, his influence diminished as newer recording artists embraced the disc format and the changing tastes of a modern audience.

End of Career and Legacy

Len Spencer passed away on December 15, 1914, just as the recording industry was entering a new technological era. His death marked the end of an important chapter in early American entertainment. Spencer had been one of the first true stars of recorded sound, and his contributions to the cylinder era had helped define what was possible in early audio entertainment.

Although his later career didn’t reach the same heights as his cylinder-era success, Spencer’s influence on recorded comedy and spoken-word performance was undeniable. His work paved the way for future generations of comedic performers who would use recorded sound as their primary medium. In a sense, Spencer laid the groundwork for modern audio entertainment, helping to shape the way people experienced humor and storytelling through sound.

Spencer’s legacy lives on in the surviving recordings he made on wax cylinders and discs, which offer a rare glimpse into the earliest days of the recording industry. Today, collectors and historians continue to study and celebrate his work, recognizing him as a pioneer who helped bring vaudeville, comedy, and performance into the homes of everyday Americans. His role in early recording history is secure, and his legacy as one of the pioneering figures in American entertainment endures.

Listen

My Gal is a High Born Lady

I Don’t Care if you Never Comes Back

C-H-I-C-K-E-N Dats da Way to Spell Chicken