The Societal Impact of Early Photography

By admin / October 10, 2024 / No Comments / The Evolution of Photography

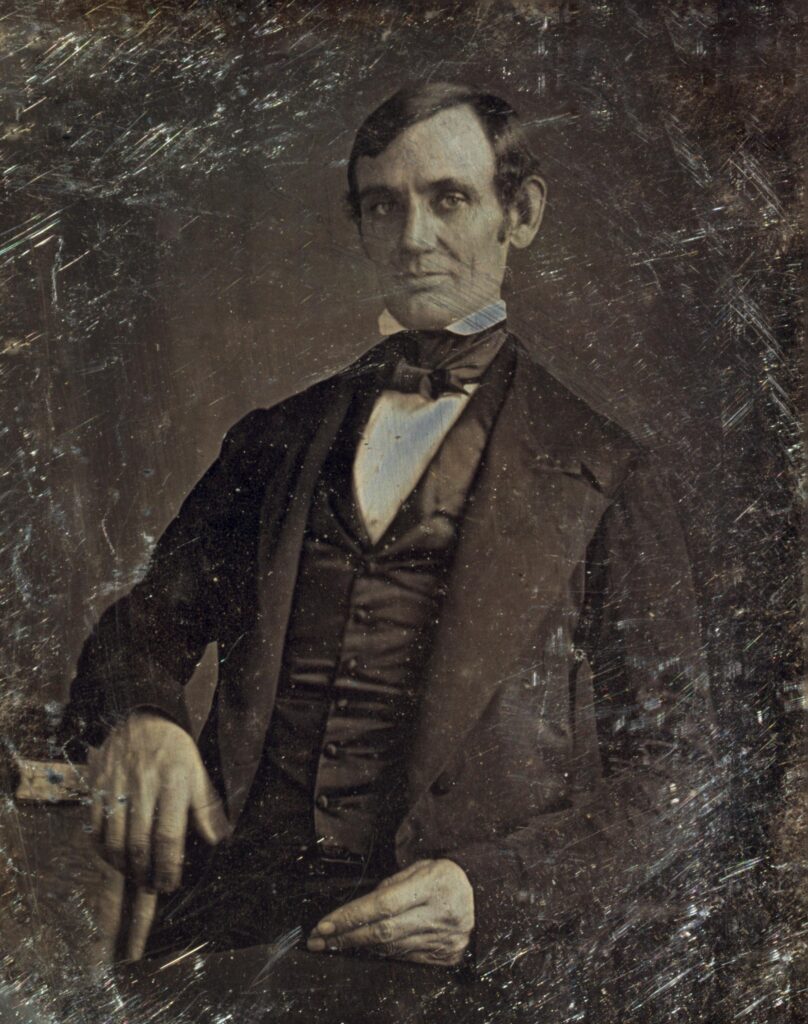

The Era of Daguerreotypes

Changing Perceptions

How Early Photography Altered the Way People Viewed Themselves—and the World

When early photography arrived—especially the daguerreotype—it quietly rewired how people understood themselves and their place in the world. Before this moment, having your likeness preserved was largely a privilege of wealth. If you wanted a portrait, you commissioned a painter, and painters did what painters have always done: they softened edges, flattered faces, and told a slightly better story than reality strictly allowed.

Photography didn’t do that. Or at least, not at first.

The daguerreotype offered something startlingly new: a way to be seen as you actually were. Lines, posture, uncertainty, pride—it all came through. And suddenly, this wasn’t just for the elite. Ordinary people could sit still for a few long seconds and walk away with proof that they existed, that they mattered, that their face was worth remembering.

That mattered more than we often give it credit for.

For the first time, families could preserve not just names and stories, but faces. Real ones. The result was a deeper, more intimate connection to memory. A photograph wasn’t an interpretation—it was a moment, frozen and handed forward to people not yet born.

The Rise of Portrait Photography

As portrait photography spread, it quietly became one of the most important historical record-keeping tools we’ve ever invented. Daguerreotypes didn’t just capture individuals; they captured class, fashion, confidence, exhaustion, hope. They recorded people who would never appear in history books, but who nevertheless lived full, complicated lives.

These images now serve as windows. Hairstyles, clothing, posture, even expressions tell us how people wanted—or didn’t want—to be seen. Taken together, early portraits form a visual archive of everyday humanity. Not kings and generals, but shopkeepers, children, laborers, couples trying to look calm while holding very still.

Accessibility and the Slow March Toward Democratization

Early photography wasn’t cheap or easy. Sitting for a daguerreotype took time, patience, and money. But technology has a habit of shrinking barriers. As photographic processes improved and equipment became more practical, photography drifted out of elite studios and into the reach of the middle class.

This shift mattered enormously. Photography stopped being a novelty and became a habit. A way of marking time. A way of saying: this happened.

With new processes and more portable equipment, photography became something people used, not just something they observed. It turned into a tool for identity, memory, and expression—and once that door opened, it never really closed again.

Photography Steps Into the World

It didn’t take long for photographers to realize they weren’t limited to studios. Cameras went outside. Into streets, battlefields, factories, gatherings, and moments of upheaval. Photography became a witness.

For the first time, the public could see events rather than just read about them. This changed journalism permanently. Images carried emotional weight that words alone rarely could. They shaped opinion, stirred empathy, and created shared reference points for society at large.

Art, Anxiety, and Adaptation

Not everyone welcomed photography with open arms. Painters, especially portrait artists, understandably worried. If a machine could capture reality faster and cheaper, where did that leave them?

But art has always evolved alongside new tools. Many artists didn’t fight photography—they used it. Photographs became references, studies of light and composition, aids rather than enemies. In doing so, both mediums grew. Painting leaned into interpretation and abstraction. Photography explored realism, mood, and eventually, artistry in its own right.

Early Photographs as Time Machines

Today, daguerreotypes feel almost magical. Tiny, reflective, fragile—they demand attention. When you look at one, you’re not just seeing an image. You’re standing face-to-face with someone who had no idea you’d ever exist.

These photographs have become precious historical artifacts not because they’re rare, but because they’re honest. They preserve the mundane alongside the monumental. They show us how people lived, dressed, loved, and endured.

Closing Thoughts

Early photography changed everything. It shifted power, widened access, and redefined how memory works. It allowed people to see themselves clearly—and to be seen by others, long after they were gone.

The daguerreotype didn’t just capture images. It captured humanity in transition: stepping into modernity, blinking slightly at the light, and holding still just long enough to be remembered.

And honestly? We’re still living in the shadow of that moment.

Early Daguerrotypes